How the world’s fastest sail racing boats fly above the water

Tune in to SailGP Season 2 and you’d be forgiven for thinking that your eyes are deceiving you.

So, what is foiling, how does it work, and when did sailing become so… cool?

It's all about drag

The story behind hydrofoils

The next frontier.

Beneath The Surface

Watch on youtube.

Access All Areas

Want to learn more about SailGP?

Meet the denmark sailgp team, find all the latest news, go beneath the surface of sailgp, discover more beneath the surface.

Protecting paradise – Sailing towards a more sustainable future

Like so many coastal communities all over the world, preserving the delicate marine ecosystem and the health of the ocean is of huge priority on the island of Bermuda

Chasing a dream – Risking everything to renovate an abandoned hotel

When builder Bryan Baeumler stumbled upon a decaying and abandoned resort on the tropical island of St. Andros in the Bahamas, he was compelled to quit his cosy life in Canada and transform the ruin into a luxury escape. His top priority when revitalising the dilapidated resort was to renovate in the most sustainable way possible, with true respect for its island location. But how could this be done?

The Beneath The Surface show

We go Beneath The Surface of SailGP's iconic host cities, set a spotlight on great projects and curious mind and catch all the lastest with the Denmark SailGP Team. Join us as we travel the world and explore how innovation and science is helping solve the world's biggest challenges!

Helping Taranto sail towards a brighter horizon

Taranto, and other parts of the southern region, has long suffered from brain drain. But can the renovation wave that is currently sailing through Italy help reverse this trend and breathe new life into this once charming city?

ROCKWOOL Group

LATEST NEWS

Seafair 75 Saturday Heat Recap

Walt Ottenad 2024-09-14T09:40:11-07:00 Race Results , Seattle |

Saturday Heat Recap: Following the morning second qualifying session, the H1 Unlimited hydroplanes took to the race course for a total of four heats on Saturday afternoon. In the first [...]

Seafair Qualifying Report

Walt Ottenad 2024-08-04T05:39:14-07:00 Race Results , Seattle |

H1 UNLIMITED LAUNCHES HYDROS & HEROES INITIATIVE

Walt Ottenad 2024-09-14T09:39:59-07:00 H1 Unlimited News |

STATEMENT ON UPDATED MADISON QUALIFYING ORDER

Walt Ottenad 2024-07-06T07:34:56-07:00 H1 Unlimited News |

Guntersville Saturday Recap

Walt Ottenad 2024-07-02T08:24:29-07:00 Race Results , Guntersville |

LATEST NEWS

Mercurys Coffee APBA Gold Cup Sunday Recap

Walt Ottenad 2024-09-16T07:44:30-07:00 September 16th, 2024 |

Mercurys Coffee APBA Gold Cup Saturday Recap

Walt Ottenad 2024-09-16T07:50:49-07:00 September 15th, 2024 |

Mercurys Coffee APBA Gold Cup Friday Recap

Walt Ottenad 2024-09-14T09:39:03-07:00 September 14th, 2024 |

Mercurys Coffee to Title Sponsor San Diego Bayfair APBA Gold Cup

Walt Ottenad 2024-09-10T15:57:10-07:00 September 10th, 2024 |

Apollo Mechanical Cup Weekend Recap

Walt Ottenad 2024-08-05T08:11:01-07:00 August 5th, 2024 |

Walt Ottenad 2024-09-14T09:40:11-07:00 August 4th, 2024 |

H1 UNLIMITED VIDEO

Over 3000 videos can be found on our YouTube channel where we present our Live Stream from each race event, the best of our Onboard footage, TV coverage and other interesting videos that show the incredible speed, beauty and violence of Unlimited Hydroplane racing. Be sure to SUBSCRIBE to the H1 Unlimited channel to be notified whenever we add footage, and please share with friends!

Hit the VIDEOS page to see all of our full race and onboard videos back to the 2011 season, and watch our latest videos at left

2024 LIVE STREAM:

Every session of every race on the 2024 schedule will be streamed live to YouTube, available for free on any device. Be sure to check in on your preferred device or here at H1unlimited.com during every race weekend to see all the action LIVE!

H1 UNLIMITED PRE-SEASON TEST: MAY 31

Guntersville lake hydrofest: june 29-30, madison regatta: july 5-7, tri-cities columbia cup: july 26-28, seafair apollo cup: august 2-4, san diego bayfair: september 13-15, h1 unlimited video library.

The H1 Unlimited YouTube channel has over 3900 videos, including thousands of Onboard Videos, hundreds of live event videos and dozens of compilations from our exciting races!

For a race-by-race recap of all seasons dating back to the 2011 season, visit the “VIDEOS” page from the menu and visit the YouTube channel to see the latest content and follow H1 Unlimited Hydroplane Racing during the upcoming 2023 season!

Watch some of our latest videos below, hit the H1 YouTube channel and SUBSCRIBE!

ABOUT H1 UNLIMITED

The Unlimiteds are powered by turbine-engines that produce around 3,000 horsepower and World War 2-era Allison V-12’s that kick out around 2,500 horsepower – allowing our drivers to reach speeds of nearly 200 mph and producing a massive 60-foot tall, 300-foot long wall of water called a “roostertail” behind them. With very few restrictions, these majestic hydroplanes race in front of shorelines packed with fans on bodies of water throughout the United States.

Follow the H1 Unlimited Hydroplane Racing Series in 2024:

The season kicks off June 29-30 in Guntersville, Alabama, home of the Guntersville Lake Hydrofest . We will return to this ultra-fast course layout where the third-fastest lap of all time was set in 2023!

From there, the boats head to Madison, Indiana, home of the only community-owned hydroplanes on the circuit for the Madison Regatta on the Ohio River July 5-7.

The next stop is the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington July 26-28 for the Apollo Columbia Cup and a sunbaked weekend on one of the super speedways of the series – look for speeds topping 200 mph.

Seattle’s Seafair is next up on August 2-4. As the home race for most of the Unlimited teams, everyone wants to win the Seafair Apollo Mechanical Cup!

We’re back to San Diego after a year away on September 13-15. Beautiful Mission Bay never fails to provide the perfect backdrop for our fast boats.

If you haven’t experienced H1Unlimited hydroplane racing in person, choose an event, get down to the shore and see what makes this “the most spectacular sport on the water.”

© 2024 H1 Unlimited. H1 Unlimited is a registered trademark of the American Boat Racing Association. | Privacy Policy

2015 Year In Review:

2016 year in review:, 2017 year in review:, 2018 year in review:, 2019 year in review:, 2021 year in review:, 2022 year in review:.

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- The Big Story

- Newsletters

- Steven Levy's Plaintext Column

- WIRED Classics from the Archive

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Data Supercharges Billion-Dollar Boats in the World’s Fastest Sailing Race

As billion-dollar catamarans skim across the ocean vying to best each other in the world's fastest sailing race, the win may not always go to the best sailors. Sometimes, a victory in the America's Cup goes to the team with the best data.

"This is as much a design race as a sailing race" says Mauricio Munoz, an engineer for the British Land Rover BAR team . Munoz's team is one of many in the 2017 America's Cup who used data collected during pre-Cup races to improve the designs of their boats. "Design without data, well I'm not sure what it is," Munoz says.

During these head-to-head races—where teams from around the globe sail as fast as 30 knots—even a half-knot gain in speed can be all that's needed to secure a victory. And since a tweak to a boat's design or to the crew's routine is often enough to earn it that extra brio in the water, the more data about the boat's performance that can be gathered, the better.

Thousands of sensors mounted all over the catamarans—from the tip of the sail to the hydrofoil under the boat—record every moment of action during a race, from boat speed and wind data to the various forces stressing the different sections of the craft. Teams can collect up to 16 gigabytes of data per day. In Land Rover's case, the team streams its data to a chase boat in real time. Later, a team back home in England virtually replays the day on the water, synchronizing video of the race with the sailing metrics. This analysis informs sailors of tactical advantages and gives engineers clues about how to build a better boat.

"This is a game all about being quick and being flexible and being able to spot things right when they happen and feed the info back to the coach, sailing team, and design team," says Munoz. Early in the Land Rover BAR's formation, the collected data helped inform the boat's design. As the race neared, the data offered strategic insight. The effort paid off: During the most recent America's Cup, held at the end of June in Bermuda, Land Rover BAR qualified for the challenger playoffs in its first-ever attempt before losing to the eventual 2017 champion, Emirates Team New Zealand.

Land Rover isn't the only team gobbling up metrics. Scott Ferguson, the design coordinator for Team USA Oracle , stays on the Oracle chase boat as a Wi-Fi system transmits data from the racing boat. Ferguson conducts real-time analysis on the chase boat before sending it to the shore for later study.

"As technology grows, we are getting more and more and better information," Ferguson says.

In addition to collecting data from hundreds of on-boat sensors, Oracle also captures video using GoPro cameras aimed at the rudders and boards. Pairing the video with data allows for an even deeper understanding of the numbers, Ferguson says.

In the case of Land Rover BAR, Munoz says the obscene amounts of data his team collected helped improve its catamaran design. In the year between the time the boat was built and the first America's Cup races, Munoz built computer models using data collected on the boat's top-performing days. What different strategies did the sailors take in certain wind conditions, and what speeds did they reach? What tactics proved fastest in key turns?

"Without saying too much, some of the (foils) you see fitted on the boat—the decision to make those and implement certain design decisions on those boards come from input form this particular research," Munoz says. "It is the same thing with the rudders."

After spending years crunching data to refine both the crew's tactics and the boat's design, Munoz says watching Land Rover BAR's on-water speed during the America's Cup was all worth it. "Seeing it out on the water and winning races as a first-time contender is definitely worth the sacrifice," he says. "Without this (data) we would never have been able to reach these conclusions."

Follow Tim Newcomb on Twitter at @tdnewcomb .

SP80 aims to have the fastest sailboat in the world next year. See photos of the futuristic craft poised to break records.

- Company SP80 is trying to break the world record for the fastest sailboat.

- The fastest sailboat speed is currently 65.45 knots — SP80 is gunning for 80 knots, or 92 mph.

- The SP80 boat was displayed at this year's Monaco Yacht Show.

With its slender frame, white exterior, and extraterrestrial vibe, SP80 is looking to break the record for the world's fastest sailboat.

Although the SP80 boat, displayed "ready-to-sail" for the first time this year's Monaco Yacht Show , looks like it would be powered by rocket fuel, a giant kite pulls the vessel along with the wind, Laura Manon, a spokesperson for SP80, told Insider.

"We talked to hundreds of people over the week, and they were all amazed that it was a sailboat with no engine on board," Manon said of the yacht show.

Manon continued: "People in Monaco said it looked more like a submarine or an airplane, and someone even thought it was a drone!"

The French company, started by pals Mayeul van den Broek, Xavier Lepercq, and Benoit Gaudiot in 2018, hopes to use its analog tech to reach 80 knots, or 92 mph, and shatter the 65.45-knot record held by Paul Larsen and his Vestas Sailrocket 2.

Luxury watchmaker Richard Millie, known for its collaborations with Formula 1 , became SP80's title partner to support the venture.

However, despite the team's four-year investment in the project, the boat itself is still in early testing phases. The boat touched water for the first time in early August at Lake Geneva and could withstand being pulled by a speedboat at 30 knots, per a press release on the site — still a far cry from the 80 knots the team is looking to hit.

Related stories

The SP80 boat is 34 feet long, 25 feet wide, and weighs about 330 pounds, per the company's site . In the front is a cockpit for two: One pilot controls the kite, while the other steers the boat. The carbon fiber build is reinforced with Kevlar for added protection in case of a collision, and pilots are strapped down and given helmets and emergency oxygen masks.

The SP80 appears ready to blast off; however, every detail of the boat is designed to ensure it doesn't actually fly.

"At the very high speeds we are targeting, we don't want to fly but to stay really flat on water, kind of like Formula 1," Manon told Insider.

Underneath the boat is a uniquely slanted hydrofoil , built to keep the vessel in the water as the attached kite pulls it to top speeds.

"The boat has three contact points with the water: the main hull and two side floats. At the rear the power module constantly aligns the kite's ascending force, which pulls the boat up, with the foil force that pulls it down," Mayeul van den Broek, CEO of SP80, explains in the video.

As for what's next for the team, the company says the boat is headed to the south of France for further testing as they race for the world record — which they hope to attempt in 2024.

Manon said the team will attach a smaller kite, allow the pilots to start feeling comfortable with the vessel, and gradually increase the speed using larger kites. The goal, Manon said, is to first break the 65 knot record and "then to continuously accelerate until 80 knots."

Watch: The eFoil surfboard lets you fly above the water

- Main content

Sail GP: how do supercharged racing yachts go so fast? An engineer explains

Head of Engineering, Warsash School of Maritime Science and Engineering, Solent University

Disclosure statement

Jonathan Ridley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

Sailing used to be considered as a rather sedate pastime. But in the past few years, the world of yacht racing has been revolutionised by the arrival of hydrofoil-supported catamarans, known as “foilers”. These vessels, more akin to high-performance aircraft than yachts, combine the laws of aerodynamics and hydrodynamics to create vessels capable of speeds of up to 50 knots, which is far faster than the wind propelling them.

An F50 catamaran preparing for the Sail GP series recently even broke this barrier, reaching an incredible speed of 50.22 knots (57.8mph) purely powered by the wind. This was achieved in a wind of just 19.3 knots (22.2mph). F50s are 15-metre-long, 8.8-metre-wide hydrofoil catamarans propelled by rigid sails and capable of such astounding speeds that Sail GP has been called the “ Formula One of sailing ”. How are these yachts able to go so fast? The answer lies in some simple fluid dynamics.

As a vessel’s hull moves through the water, there are two primary physical mechanisms that create drag and slow the vessel down. To build a faster boat you have to find ways to overcome the drag force.

The first mechanism is friction. As the water flows past the hull, a microscopic layer of water is effectively attached to the hull and is pulled along with the yacht. A second layer of water then attaches to the first layer, and the sliding or shearing between them creates friction.

On the outside of this is a third layer, which slides over the inner layers creating more friction, and so on. Together, these layers are known as the boundary layer – and it’s the shearing of the boundary layer’s molecules against each other that creates frictional drag.

A yacht also makes waves as it pushes the water around and under the hull from the bow (front) to the stern (back) of the boat. The waves form two distinctive patterns around the yacht (one at each end), known as Kelvin Wave patterns.

These waves, which move at the same speed as the yacht, are very energetic. This creates drag on the boat known as the wave-making drag, which is responsible for around 90% of the total drag. As the yacht accelerates to faster speeds (close to the “hull speed”, explained later), these waves get higher and longer.

These two effects combine to produce a phenomenon known as “ hull speed ”, which is the fastest the boat can travel – and in conventional single-hull yachts it is very slow. A single-hull yacht of the same size as the F50 has a hull speed of around 12 mph.

However, it’s possible to reduce both the frictional and wave-making drag and overcome this hull-speed limit by building a yacht with hydrofoils . Hydrofoils are small, underwater wings. These act in the same way as an aircraft wing, creating a lift force which acts against gravity, lifting our yacht upwards so that the hull is clear of the water.

While an aircraft’s wings are very large, the high density of water compared to air means that we only need very small hydrofoils to produce a lot of the important lift force. A hydrofoil just the size of three A3 sheets of paper, when moving at just 10 mph, can produce enough lift to pick up a large person.

This significantly reduces the surface area and the volume of the boat that is underwater, which cuts the frictional drag and the wave-making drag, respectively. The combined effect is a reduction in the overall drag to a fraction of its original amount, so that the yacht is capable of sailing much faster than it could without hydrofoils.

The other innovation that helps boost the speed of racing yachts is the use of rigid sails . The power available from traditional sails to drive the boat forward is relatively small, limited by the fact that the sail’s forces have to act in equilibrium with a range of other forces, and that fabric sails do not make an ideal shape for creating power. Rigid sails, which are very similar in design to an aircraft wing, form a much more efficient shape than traditional sails, effectively giving the yacht a larger engine and more power.

As the yacht accelerates from the driving force of these sails, it experiences what is known as “ apparent wind ”. Imagine a completely calm day, with no wind. As you walk, you experience a breeze in your face at the same speed that you are walking. If there was a wind blowing too, you would feel a mixture of the real (or “true” wind) and the breeze you have generated.

The two together form the apparent wind, which can be faster than the true wind. If there is enough true wind combined with this apparent wind, then significant force and power can be generated from the sail to propel the yacht, so it can easily sail faster than the wind speed itself.

The combined effect of reducing the drag and increasing the driving power results in a yacht that is far faster than those of even a few years ago. But all of this would not be possible without one further advance: materials. In order to be able to “fly”, the yacht must have a low mass, and the hydrofoil itself must be very strong. To achieve the required mass, strength and rigidity using traditional boat-building materials such as wood or aluminium would be very difficult.

This is where modern advanced composite materials such as carbon fibre come in. Production techniques optimising weight, rigidity and strength allow the production of structures that are strong and light enough to produce incredible yachts like the F50.

The engineers who design these high-performance boats (known as naval architects ) are always looking to use new materials and science to get an optimum design. In theory, the F50 should be able to go even faster.

- Engineering

- Aerodynamics

Chief People & Culture Officer

Lecturer / senior lecturer in construction and project management.

Lecturer in Strategy Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Education Focused) (Identified)

Research Fellow in Dynamic Energy and Mass Budget Modelling

Communications Director

- AROUND THE SAILING WORLD

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Email Newsletters

- America’s Cup

- St. Petersburg

- Caribbean Championship

- Boating Safety

- Ultimate Boating Giveaway

World’s Fastest Sailboat: Quantum Leap

- By James Boyd

- Updated: June 18, 2013

Vestas SailRocket 2

Last November, in southwest Africa, a landmark moment occurred in the history of sailing when Paul Larsen pegged the outright world sailing speed record. In recent years the record was eclipsed in small increments, usually a fraction of a knot, but the Australian’s innovative Vestas SailRocket 2 flew down the 500-meter course at an average speed just over 75 mph, almost 10 knots faster than the previous record held by American kiteboarder Rob Douglas.

Tim Colman’s asymmetric Crossbow established the first 500-meter record in 1972 with a heady 26.3 knots. Windsurfers took hold of the record in 1986 and held it until 1993 when Simon McKeon’s asymmetric yacht Yellow Pages took it and held it until 2004. Windsurfers reigned again for a few years, but it was the kiteboarders who shattered the mythical 50-knot barrier in 2008. In 2009 Alain Thebault’s foiler L’Hydroptère managed 51.36 knots. But the kiteboarders quickly won it back when Douglas pushed the record to 55.65 knots.

With the latest record Larsen not only reclaimed it on behalf of “the boats,” but set a benchmark—65.45 knots to be precise—that will be hard to surpass.

Despite the stunning margin of increase, the record did not come easily. The feat was the culmination of 10 years of hard graft, fiscal uncertainty, and severe setbacks.

The Australian-born Larsen had been best known in the sailing world for his offshore adventures. He crewed on Pete Goss’s ill-fated Team Philips , then ended up sailing around the world in The Race with Tony Bullimore. He completed another lap aboard Doha 2006 , winner of the Oryx Quest.

In 2002, he and his Swedish girlfriend, Helena Darvelid, herself an accomplished offshore sailor, teamed up with English naval architect and speed sailing junkie Malcolm Barnsley.

The catalyst for the SailRocket project was the book The 40-knot Sailboat written in 1963 by American rocket scientist and yacht design visionary Bernard Smith. At a time when yachts still had long keels, Smith described the idea of a sailing vessel dubbed the “aero-hydrofoil” with neutral stability: where the heeling moment from the rig is completely offset by a foil located to windward. Smith built models to prove his concept, but it was only when the first Vestas SailRocket was launched in the spring of 2004 that his concept was proven at full scale.

Initial progress was slow. In 2005, after two seasons getting to know the platform, they replaced its softsail rig with a wing. The first trials with the boat were on Portland Harbour, close to Larsen and Darvelid’s home in Weymouth, Great Britain. In 2007, the duo decamped to Walvis Bay, Namibia, a venue with perfect characteristics that offered more opportunity to carry out runs: a gently sloping beach, regular winds, and a 1,000-meter stretch of obstruction-free water. In recent years, Namibia has taken over from The French Trench in Saintes Maries de la Mer, France, as the preferred location for breaking sailing speed records. All the speed records set by kiteboarders were done in Luderitz, Namibia, some 250 miles south of Walvis Bay.

The first big speeds came in 2007, with SailRocket hitting an instantaneous speed of 42.4 knots during one run. It was well short of the record at the time, but fast enough to prove Smith’s concept. That number also enabled Larsen and Darvelid to gain vital sponsorship from wind turbine manufacturer Vestas.

With such a groundbreaking boat, teething problems were inevitable. They were getting faster, but the boat, rather than the pilot, was still mostly in control. A significant issue was the steering. “The back of the boat looked like Edward Scissorhands,” says Larsen. “We had three rudders hanging off the back; one system was confusing the other. It was a mess.”

After nearly destroying the boat in a crash, Larsen and Darvelid, along with Barnsley and engineer George Dadd, set out to create a better steering system. With this fitted, and_ Vestas SailRocket_ rebuilt, they set off again, as Larsen says “on one of the wildest runs I’ve ever had in that boat.” The steering was better—the boat would bear away to some degree—but far from perfect. On one run, Vestas SailRocket ran onto the beach at 35 knots.

But despite the troubles controlling the boat, Larsen knew they were on the right track. After tweaking the rudder over the next few days, they did one run, in big winds and relatively rough conditions, where Larsen felt for the first time that he was in control of the beast. It was a landmark moment.

“After that run, we booked the WSSRC for the first time,” he says, referring to the World Speed Sailing Record Council, which administers and validates all sailing speed records.

While the boat continued to get faster, a more fundamental design issue became apparent. With the pilot’s seat in the rear of the main hull, trying to keep the boat pointed in the right direction was a challenge. It was, Larsen describes, “like trying to fly an arrow backwards. It would try to turn around and fly the proper way with the weight at the front and the feathers at the back, by turning laterally into the wind, or vertically if it had to.”

On one memorable occasion, Vestas SailRocket took off and performed a complete backflip, leaving Larsen upside down in the water and the boat once again in pieces. The video of this crash went viral on YouTube and has been played more than 400,000 times. But this was one of many incidents: “We had rounded up into the wind, smashed the wing, and folded up the beam at least four times before we even got to the flip,” he recalls. “Each one of those was a big crash, big repair, damaged wing, broken struts; once we got the boat going really quick, then she started to somersault.”

Amid all of this, the world record was being pushed further down the track by the kiteboarders with Douglas stealing it from the windsurfers and then Frenchman Sebastien Cattelan being the first sailor to break the 50-knot barrier. But Vestas SailRocket also made its mark. The same day as the backflip, SailRocket became the world’s fastest boat, as opposed to board, at a speed of 47.3 knots.

The following season Larsen and company realized time was running out for Vestas SailRocket . They had an unofficial run of 49.38 knots and a peak speed of 52.78 knots, but the runs were still very much do or die. Larsen endured another full backflip and a separate catastrophe when the forward beamstay broke, causing the beam to fly back into the main hull and the boat to fold up, putting the pilot in the hospital. “It went from over 47 knots to a standstill, and the beam came back at me like a cricket bat,” says Larsen. “I still rate that as the most violent crash in yachting yet.”

With Vestas SailRocket reaching the limit of its potential, the team was already deep into the design of Vestas SailRocket 2 , harnessing all the knowledge they’d learned from the first boat.

While Barnsley spearheaded the design of the first boat, the principle designer of the second was Chris Hornzee-Jones, a structural engineer and aerodynamicist, who heads the company AeroTrope and designed the wingsail for the first Vestas SailRocket .

Launched in March 2011, Vestas SailRocket 2 incorporated all the fundamental features of the first boat: a hull to windward incorporating the all-important foil, a single crossbeam, and a wingsail inclined to weather by 30 degrees. In other ways, however, it was a significant step forward. At 40 feet long by 40 feet wide, it was slightly bigger, and the hull was now more like a glider fuselage sitting on two short floats at the bow and stern, with the rudder mounted on the forward one. To leeward the wingmast sat atop a third float.

Most noticeable was that while the floats pointed in its direction of travel, the fuselage was offset to starboard by 20 degrees to point into the direction of the apparent wind in order to minimize drag at high speed. They also “reversed the arrow,” putting the cockpit in the bow of the fuselage. They enlarged the wing from 172 sq. ft. to 193 sq. ft., added a hooked section at the bottom of the wing (giving it a hockey stick profile), which acts as an endplate for the wing and also provides some control over how high the leeward float flys.

In the cockpit, in addition to the steering wheel, the controls Larsen uses during a run are the mainsheet and the control for the flap on the outboard extension of the wing. There are also controls for raising and lowering the main foil and the low-speed skeg, and controlling the wing when stationary.

During the 2011 season, the team made solid progress. Vestas SailRocket 2 proved more controllable and stable than the previous boat, and in two seasons of use it experienced none of the same catastrophes that afflicted the first boat. However, regardless of the wind speed, the new boat couldn’t surpass the low 50-knot range. By this stage, Douglas had pushed the record to 55.65 knots.

The culprit proved to be the foil, mounted on a bracket well aft on the windward side of the fuselage.

In 2011, the team trialed two foils. Both were L-shaped, one a conventional asymmetric teardrop shape—with a similar section to an IMOCA 60/Volvo 70 daggerboard—the other a ventilating foil. With the former both the low- and high-pressure sides of the foil are put to use, but when traveling at speeds approaching 60 knots the foil cavitated. This is a common problem for propellers, caused when pressure on the low-pressure side of the foil becomes so low it causes the water to vaporize, effectively detaching it from the foil. With only one side of the foil working, the performance of the foil drops suddenly, with potentially disastrous effects.

A ventilating foil with more of bullet shape (a sharp leading edge, and a blunt trailing edge) is, in hydrodynamic terms, much less efficient: Its effective working area is much reduced, and it creates more drag. However, this shape theoretically removes the cavitation issue and allows the foil to operate smoothly at speeds well in excess of those where a conventional foil starts to struggle. During the 2011 season Vestas SailRocket was mostly being sailed with this foil, only it failed to ventilate properly. In desperation the team took out the grinder and progressively shortened the foil in 6″ chunks, down from 3’3″ to 1’9″, before returning to base to consider the data.

Back in Great Britain, the team planned to build a new foil, but was unsure what exactly to build. Talking to the experts only caused more confusion. They were advised a ventilating foil shouldn’t be able to get beyond 30 knots, but they had achieved speeds in excess of 50 knots with it. So they reverted to their original concept of a ventilated foil, only a depth of around 2′ submerged and a chord of 10″ at its maximum—about 60 percent of its original area. They also fitted Cosworth data loggers to the foil to establish where cavitation or ventilation was occurring.

The eureka moment came not with the new foil on its own, but when they added a strategically placed fence to prevent ventilation in an area of the foil that shouldn’t have been ventilated. And the rest, as they say, is history. Initially they set a new record of 59.23 knots, and 10 days later Larsen managed 65.45 knots with a peak speed of 67.74 knots.

What’s it like at 60 knots? “It depends on how close I get into the beach,” says Larsen. “If I stay out of the rough stuff, it is a short, sharp, bumpy ride, like on a high speed powerboat. This thing doesn’t knife through the waves, it skips over the top of the small chop. At the back of the boat it is pretty good, just riding on a foil, it is pretty civilized. The visibility is brilliant. I have got no sunglasses or visor on. There is no spray coming into the cockpit, compared to the last boat. I only feel a little bit of spray just when I start up.”

At present there are no plans to progress with Vestas SailRocket . The point has been proven. From the heavens Bernard Smith, who passed away on Feb. 10, 2010, can smile. Larsen is adamant the concept will go faster; in theory there is nothing to stop this genre of boat from hitting 100 knots. But it will require another foil. With his offshore background Larsen is intrigued to see if the neutral stability concept can be developed for more practical applications, but only if it makes boats like the 131-foot Banque Populaire maxi tri [the outright ’round the world record holder at 45 days] look like pedestrian dinosaurs.

- More: Best of 2013 , Boatspeed , Sailboats

- More Sailboats

Sporty and Simple is the ClubSwan 28

Nautor Swan Has A New Pocket Rocket

Pogo Launches its Latest Coastal Rocket

A Deeper Dive Into the Storm 18

INEOS Britannia Advances, American Magic Wins Two To Keep Series Alive

Marblehead’s Corinthian Repeats at Resolute Cup

Mustang Quadra DrySuit Does More With Less

Alinghi and American Magic Wins Keep Louis Vuitton Cup Semis Alive

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

How Fast Do Racing Sailboats Go?

Speed thrills, and in a sailboat, it thrills even more. Sailboat racers like to push their boats to the limit. But just how fast do racing sailboats go?

Sailboats come in a variety of shapes and sizes. If you are a speed enthusiast, you must wonder about the maximum speeds of different sailboats and if larger sailboats can go faster than smaller ones.

Racing sailboats usually skim over the water at around 15 to 20 knots. For comparison, the average speed of a traditional sailboat is only around 5 to 8 knots. Some custom-designed boats can reach record-breaking speeds of up to 50 or more knots.

Since sailboats don't rely on internal power for speed, many factors determine the speed of a sailboat, and every sailboat has different top speeds.

Experienced sailboat sailors believe that several factors influence the top speed. The size and shape of the boat, sails, and skill level all play a crucial role in determining the speed of a sailboat. Even more than the internal factors, external factors such as the waves and the wind can greatly boost or hinder sailboat speed.

Table of contents

What Influences Sailboat Speed

Sailboats have different shapes and sizes, and different sailboats can reach different speeds. There are many internal factors, such as those related directly to the boat, and external factors, such as weather, ocean currents, etc., that influence the speed of a sailboat.

Boat Size and Length

The most crucial thing that plays a role in speed is the sailboat's length and overall surface area. What does size have to do with speed, you ask? For a sailboat to go fast, you need to maximize the propulsion by the wind and keep drag and resistive forces to a minimum.

As the sailboat moves through the water, it generates waves. One wave that is created among others constantly rides with the boat. It has its peak just in front of the bow, while its trough is at the stern. If this wave is long enough, it can act as a wall of water to the boat.

The aerodynamic shape of the bow is designed to push up and rise above this wave. This allows the boat to lift the bow out of the water and rise above the water surface. As the bow rises, the stern gets pushed down into the water. This reduces the drag and also allows the boat to glide above waves.

But this wall of water creates resistance for the boat, and the sailboat requires power and momentum to break through this resistance. A larger sailboat has more momentum, which allows it to break through the barrier easily. This makes it possible for the larger boat to go faster.

You might think that a smaller boat is lighter and will offer less resistance and drag. Yes, this is true, but a smaller boat generates multiple small waves, which offer more resistance. Lightweight boats are also more susceptible to wind shear and tend to veer off course.

Different boats have different hull designs. The hulls are designed to be narrow and precisely engineered for racing sailboats to offer minimum resistance. It makes sense that a boat with a hull like a bathtub will not even come close to a sailboat with a narrow and streamlined hull.

The hull design also plays a vital role in the speed of a sailboat. A hull built for speed will have a straight line from the lowest point to the aft, and the aft will be wider. This design makes the boat stable and allows it to reach higher speeds.

On the other hand, a boat with multiple curves on the hull and a narrow transom will not be as fast. The reason for the hull playing a vital role in speed is simple. It needs to cut through the water to ensure the least resistance.

There are three major hull types for sailboats.

As the name implies, monohull sailboats comprise one hull. These boats offer high levels of stability, making them extremely difficult to capsize. The hull is designed to cut through the water, which keeps the boat stable, and allows it to pick up speed. The hull can be raised out of the water if you need to go faster. Monohull boats are traditionally designed to sail below 10 knots.

A catamaran, more commonly known as a cat, comprises two hulls running side by side. These hulls are similar in size. Cats are significantly faster than monohulls and can reach between 15 knots and even go more than 50 knots.

The Trimaran is also known as the double outrigger. Trimarans have three hulls, which means they offer more stability and are extremely buoyant. The three hulls allow the boat to gain speed because it rises above the water surface with little resistance. Tamarans can reach speeds of up to 20 knots.

Skill Level

Sailboat racing has become a highly competitive sport. When it comes to speedboats, you can use engine power to hit maximum speeds, but it takes a lot of skill and experience to get your sailboat to move at speeds three times the wind.

The amount of training, skill, and experience you have is crucial to how fast your racing sailboat goes.

The only propulsion you have on a sailboat is the wind. With a good wind in your sails, your boat will move much faster. Both types of winds, apparent and true, play a crucial role in your sailboat's performance. The stronger the true winds, the faster the boat will move.

Waves play a crucial role in your boat's performance. They influence the speed and determine your and your vessel's safety. Calm and serene water can quickly turn aggressive and furious without prior notice.

If the waves are strong enough, and you don't know how to navigate through them, they can easily capsize your boat. Depending on their direction, they can also significantly increase or decrease the speed of your sailboat.

When the medium you are running on, water, is moving fast, your boat will experience a significant increase in speed. You can think of it as walking on a travelator. If you are walking in the same direction as the travelator, your speed will be increased. But, if you decide to walk in the opposite direction to the travelator, you will look weird and will be considerably slowed down.

Going Faster Than The Wind

Two types of winds influence the speed of a sailboat; these are true wind and apparent wind. To understand these better, let us look at an example. Imagine you are riding a motorcycle when there is no wind. As you pick up speed, you begin to feel the wind in your face; this is called apparent wind. It is the air pressure you feel while moving through the still air.

Say you are riding at 20 mph on your motorcycle; the wind you will feel on yourself will be 20 mph. Now let's add true wind to the equation. Say the wind is naturally blowing at 20 mph, and you are heading in the same direction as the wind. The wind pushing you and the apparent wind will cancel each other out if they are perfectly reverse-parallel to one another.

The sails experience the same apparent wind you felt while on the motorcycle when you are on the sailboat. The sails are designed to put the apparent wind to use and help propel the boat further. As you increase your speed, the apparent wind grows stronger, which leads to more wind in your sails.

How Fast do Racing Sailboats Go?

Now that we know the factors that influence sailboat speed, let us look at how fast racing sailboats go. If you are a traditional sailboat sailor, you will be lucky if you can hit 10 knots. But with racing sailboats, you can achieve over 15 knots, and many racing sailboats can hit 20 knots. The fastest anyone has ever achieved on a sailboat is 65.45 knots , a world record.

Related Articles

Positions on a Racing Sailboat

How Fast Do Catamarans Go?

Are Small Sailboats or Big Sailboats Faster?

Jacob Collier

Born into a family of sailing enthusiasts, words like “ballast” and “jibing” were often a part of dinner conversations. These days Jacob sails a Hallberg-Rassy 44, having covered almost 6000 NM. While he’s made several voyages, his favorite one is the trip from California to Hawaii as it was his first fully independent voyage.

by this author

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

Daniel Wade

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

How To Choose The Right Sailing Instructor

August 16, 2023

Basics Of Sailboat Racing Explained

May 29, 2023

Cost To Sail Around The World

May 16, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

June 15, 2022

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Sailing the fastest offshore monohull, the ClubSwan 125

- Toby Hodges

- October 19, 2021

Yachting World's Toby Hodges sails the radical new ClubSwan 125 Skorpios and gives you a tour. Skorpios is the largest entrant in the Fastnet ever and took line honours weeks after launch in 2021

It’s tricky to gauge speed and scale against anything else when you have to sail a few miles offshore to avoid dredging the English Channel. Nevertheless, sailing onboard the new ClubSwan 125, I could tell that great stretches of the UK’s coastline, passages that would normally drag by over hours, were ripping past at a velocity that made me question my knowledge of known landmarks.

Aboard Skorpios , the imposing new ClubSwan 125, we’re not talking outright silly peak speeds, but more the sheer unrelenting consistency of the high speeds. At 140ft including bowsprit, Skorpios is, by any scale, a beast which, under its substantial sail area, becomes an uncompromising, fiendishly powerful mile-muncher.

Standing at the windward helm when powered up feels so high above the water it’s akin to leaning out of a second storey window. And with over 20 top professional crew sitting on the rail in front of you it is an awesome, slightly terrifying and utterly captivating experience.

However, this is not a Swan built for helming pleasure, rather with a ruthless brief to be the first monohull home in the big offshore races and to rewrite ocean records.

Skorpios is skippered by the Spanish Olympic Tornado gold medallist Fernando Echávarri, a former Volvo Ocean Race skipper.

The adrenalin of sailing the ClubSwan 125 Skorpios is perhaps heightened by the fear of the unknown: everything about this yacht seems to be on another scale altogether. This is, by some margin, the biggest offshore racing monohull, and certainly the largest ever racing Swan. It boasts possibly the deepest draught non-lifting keel (7.4m) and the largest sailplan combination ever conceived. In short, Skorpios is a seemingly limitless source of superlatives.

Skorpios is the largest monohull to have raced in the Fastnet Race to date, and, as its designer Juan Kouyoumdjian pointed out with a certain glee, it has been issued with the highest IRC rating ever awarded.

Not that handicaps will be of concern – it’s out for line honours only. That it duly succeeded at such a task at the first time of asking is all the more impressive considering the gun for this year’s particularly boisterous Fastnet start was fired just two months after the boat splashed.

This was also the first offshore race for the yacht’s owner Dmitry Rybolovlev. Sometimes it takes an ambitious owner with a substantial chequebook to make a meaningful step forward in design and engineering, and produce a ripple effect in technology.

In the case of ClubSwan 125 Skorpios it was Russian businessman and philanthropist Rybolovlev who fell for the idea of a record breaker after tasting racing victory on his ClubSwan 50 . The contract was signed in February 2017 and, four years and a pandemic later, his near three times larger version was wheeled out of Nautor’s famous Pietarsaari yard.

Just a month after its June launch, and during an intense work up period before the Fastnet, I was invited to join Skorpios for a day’s race training.

Science project

The isle of Portland is one of the few safe ports around the English Channel with a deep enough berth for Skorpios . From Dorset’s Jurassic Coast cliffs miles to the west, a single mast stands out on the horizon and as I approach through the commercial dockyard, the scale of Skorpios seems to keep increasing. It’s simply enormous, unlike any other yacht I have seen.

Enough sail? Skorpios off the Dorset coast. The ClubSwan 125 is named after owner Rybolovlev’s famous Greek island, where Jackie Kennedy married Aristotle Onassis. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

Testing systems and sea trialling for race prep takes a significant amount of sea room on a craft of this size. Thankfully we have ideal 17-22 knot conditions to encourage a long day afloat.

“We’re going to stay two to three miles offshore and sail down to the Isle of Wight,” Fernando Echávarri announces to the crew. The quietly spoken team skipper, a Spanish Olympic Tornado champion, assembled a crack team around him during the build and seems to have the unflappable composure needed for such an endeavour.

Article continues below…

Canova – The foiling superyacht designed for comfort

Were you to somehow be teleported into foiling superyacht, Canova’s palatial master cabin while under way – and let’s face…

Video: Comanche – Matthew Sheahan gets aboard the world’s fastest monohull

Setting the start line ends in your chart plotter two days before the race may seem a little over eager,…

I crane my neck as 660m2 of black 3Di mainsail is hoisted up a mast that scales 59m from the waterline, high enough for the enormous 5.5m gaff of the squaretop to be in a totally different weather system.

“This boat’s a real science project,” says Miles Seddon, reading my mind as he joins me on the aft quarter rail. The British pro navigator has stepped aboard to give some local knowledge during the Fastnet build-up.

“There are so many systems, load sensors, fibre optics etc all trying to integrate… and all are logged at 10Hz so everyone can monitor it (aboard and ashore).”

The giant ClubSwan always sails heeled and the apparent wind never really goes aft of 80º. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

With loads too high for human power onboard the ClubSwan 125, the grunt is all left to hydraulic pumps to drive winches and movable appendages. Hence the ability to monitor all loads constantly is reassuring and educational.

Nevertheless, I recognise many of the faces of the international crew who have amassed dozens of America’s Cup , Volvo Ocean Race and Olympic wins between them. The size of this craft and its level of tech places it in a high-risk category, so the ability to sail this ‘project’ safely and to the optimum, particularly with such a short training period, requires all their skill and experience.

Key crewmembers talk sporadically through their headsets, which are covered by neck scarves to try to protect against apparent winds that are typically gale force. It’s all coded language, acronyms and target talk – we are in test pilot territory here.

thrill of a lifetime as YW’s Toby Hodges gets behind the wheel. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

As 1,300m2 of A3 (asymmetric spinnaker) is unfurled we accelerate from a 10 knot canter straight to the high teens. Then out come the J4 (jib) and IRS – the bright orange sail which rates as a storm jib – to fill the large slots and Skorpios is immediately into the 20s.

I record the angles and speeds throughout the day and, looking through these later, it’s their consistency at which I marvel. “We are sailing with nearly 2,400m2 in a 59-tonne boat – so it’s pretty powerful!” Echávarri remarks. Indeed the sail area to displacement ratio of 67.8 is mind boggling.

50% Movable ballast

“Designing a racing sailboat, able to reach a speed in the region of 15 knots upwind and that will always be faster than the wind speed downwind is something unique,” comments Juan K.

The Argentinian designer, who was aboard for our trial, explains that he chose a canting keel in order to keep the displacement under 60 tonnes, which allowed for the necessary righting moment with a smaller bulb.

However, this was not always the plan. The ClubSwan 125 was originally conceived by Nautor as more as a performance cruiser-racer with teak decks and a full interior.

The decision to remove these saved an estimated six tonnes immediately. And once the owner said he wanted to go really fast, the design was continually re-evaluated. The original keel proposal was a complex telescopic/canting mechanism, so replacing that saved another 2.5 tonnes. The interior was also adapted, designed by Adriana Monk to be very minimalist and practical for offshore sailing.

The canting angle of the keel increased from 38° to 42° and a trim tab was added. The potential lift and righting moment benefits this can give were one of the areas the crew were looking at during our sail.

sailing triple-headed makes for a lot of halyard tails and sheets to keep tidy. The smart dodger was a late addition, for protection and to keep the companionway dry. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

“With a canting keel you need another appendage to produce the required side force. That is provided here by a C-foil, a hydrodynamic asymmetrical foil, but symmetrical from port to starboard, that can be tacked each side of the boat,” Juan K explains.

He estimates that this is less weight than two daggerboards and can help the boat reach a ‘skimming’ attitude when reaching. “It doesn’t give you the performance of side foils, but without the C-foil there would be 5-7° leeway. With the foil, there is zero or even negative leeway with the keel canted.”

Then there is also the equivalent weight of an average 40ft cruising yacht in water ballast, housed in 5,000lt and 3,000lt tanks each side. These take 45 seconds to fill and 30 seconds to transfer from one side to another.

“It’s righting moment without the weight in light airs,” Juan K elaborates. When more than half the weight of the boat can be shifted from side to side, pushing the correct buttons becomes imperative.

After a couple of hours in downwind mode, we’re now somewhere south of the Island and furl to gybe. An army of muscle manhandles the trunk of furled A3 onto the deck and into a bag so it can be lifted by halyard and deposited across the aft deck in preparation for the first upwind leg.

It is while briefly parked like this that the alien noises, reverberations and discomfort start. Every element of this craft is designed around speed, so restrained like this, the giant Skorpios groans and shudders like a tethered animal and the raw vibrations are felt right through to the aft deck.

ClubSwan 125 weight and windage

We’re given a steady 20 knots true for our first beat, which is on the limit of a reef in this sea state. Yet with or without a reef, we still average 14 knots at 25° to the apparent wind.

The single C-shape daggerboard is moved hydraulically from side to side to negate leeway and when fully retracted still sticks out by 80-90cm. Sensors continually inform the crew about the loads on the board. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

The harmony of the rig and sail package on the ClubSwan 125 is impressive. Southern Spars designed the high modulus mast, 60ft boom and 23ft reaching strut in combination with sister company North Sails and its Helix structured luff technology. The company says it’s one of the most advanced rig packages it has ever delivered.

The tack points were originally designed to take much higher loads, but the advances in structural luff technology and load sharing means that these point loads have greatly reduced, project manager Bob Wylie tells me. “The J2 was originally designed for 45 tonnes, yet the current tack load is around 25 tonnes.”

Future Fibres’ Aerosix rigging minimises windage. “Considering the speeds and the close apparent wind angles you’re sailing at, everything contributes to speed,” comments Echávarri, who is most impressed with the comparative reduction in vibration this rigging brings.

The highly raked mast can be finely tuned with checkstay and backstay deflectors. “To set all the sails needs a bit of play between the mainsheet trimmer and the runner trimmer,” Echávarri explains.

“The J0, which is tacked to the bowsprit, is 550m2. So with the 660m2 main we can go upwind with about 1,200m2, which is a big load!” the skipper exclaims. Occasionally we slam through or over a wave and the vibration is gut wrenching.

Otherwise, however, it’s comparatively quiet speed sailing, with hardly any noticeable wake, just the firehose of a rooster tail spraying from the stern as Skorpios planes along continuously like a giant 49er.

Twin rudders are used for control as Skorpios always sails heeled. These have Juan-K’s trademark sawtooth profile which he compares to the tubercles of a whale. They are designed to limit drag when dipping in and out of the water and to prevent the blades from stalling.

The toe-in system, which changes the angle of attack of the rudders, is adjusted from on deck using a geared system first developed for the VO70 Groupama. “You want the windward one to have the least drag,” Juan K explains. “For downwind VMG sailing we’re looking at 11-15° heel, reaching is 20-25° and upwind is 25°. At around 21° the windward rudder stops touching the water – it’s ideal when it’s just kissing the water.”

Life at heel

While you are certainly aware of the near 30ft of beam when sailing upwind on the ClubSwan 125, it doesn’t feel like alarming levels of heel. Skorpios tracks along on its chine, while on deck the SeaDek closed cell foam decking provides excellent grip and the aft companionway and mainsheet plinth help to break up the large cockpit spaces.

The deck design is remarkably uncluttered and kept deliberately simple, meaning minimal winches and lines on deck. The use of multiple furling foresails, similar to a racing multihull or IMOCA 60, helps simplify manoeuvres. One of the neatest features is having the furler lines all lead under deck.

Sailing Skorpios requires the balancing of phenomenal sail area with moveable ballast and righting moment, while keeping the boat on a narrow (heeled) waterline beam. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

“They have to be,” comments Wylie, “imagine a 450kg sail sitting on them – they wouldn’t shift!”

A keyboard of constrictor clutches are also used under the deck and the headsails are all on halyard locks, as are the three mainsail reefs. Lights and alarms display when these locks are engaged and then there are sensors everywhere, says Echávarri – “in the hydraulics, linear sensors between cables and sails, on vertical shrouds, on winches etc.”

During our second uphill leg I spend some time at the forward end of the rail’s crew stack filming and getting duly soaked. It really hits home how relentless and potentially exhausting it is sailing in such high apparent winds. It’s little wonder IMOCAs and Ultimes have dramatically increased their protection and aero packages.

Meanwhile, out to windward the chase boat bounces along with photographer Mark Lloyd aboard trying to steady himself. Not many powerboats could keep up with the ClubSwan 125 Skorpios in these seas, but this is no ordinary tender. Theirs is a 15m carbon catamaran, complete with 1,200hp of outboard propulsion, which was built in New Zealand in parallel development with Skorpios .

“When we decided to go lighter and lighter, the anchor became a big factor,” Echávarri elaborates. With a 7.4m deep keel, Skorpios will have to rely on its anchor gear, so the tender was designed to carry and deploy the main anchor and 600kg of chain. And because of the mothership’s restrictive draught, this chase boat also has the tanks to fuel bunker, while a sawn-off bow allows it to nudge up to the transom to unload supplies and swap sails. The sheer scale of this project!

And then it happened… one of life’s golden moments. I am offered a glory spell on the wheel. We are smoking along, sheets ever so slightly cracked, making a steady 15-16 knots in 18 knots of breeze and Skorpios is like a freight train, unwavering in its speed and line.

Occasionally I glance the long way down to the leeward rail and see the whitewater shooting past. It makes me giddy. Concentrate on the numbers Toby, this is no time to lose focus.

Minimalist saloon with canting furniture. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

So much power is felt through that foam-gripped composite wheel. On the pedestals are a hydraulics cut-off, a Jonbuoy release button, a high load alarm, and controls for the canting keel and trim tab. Needless to say I keep my hands on the wheel. The sheets are left alone as we charge back towards Portland, full steam, while I try to log every second in my long-term memory bank.

When the decorated Olympic and round the world sailor Xavi Fernandez turns round from the rail and asks me how it feels on the helm, I am lost for words and simply grin.

Echávarri sums up our sail more casually; he’s concerned with stats not emotion. “Today was a good day. Let’s say we were pretty good in performance – 95-98% of VPPs, which is good when there’s still a lot to learn.”

I simply tremble with nervous adrenaline… for days.

Building a beast

“The opportunity to work together with the greatest boatbuilders, designers and technicians around the globe, was awe-inspiring,” says Leonardo Ferragamo, Nautor’s Group president. Nautor’s Swan conceived and built the yacht in Finland, but with so many teams and subcontractors involved, Skorpios is more a custom race boat than a conventional Swan.

“A team of 30 was initially brought in to laminate the hull,” says Bob Wylie, while explaining the challenge of maintaining a workforce during Covid times. Grand-Prix raceboat construction techniques were used, including unidirectional prepregs and honeycomb nomex cores, with monolithic construction below the chine.

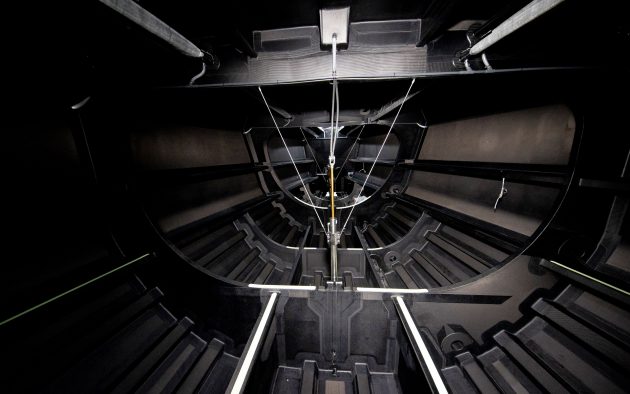

engine room contains the twin 400lt carbon hydraulic tanks and the mast base (mast jack load at full dock tune is around 90 tonnes!). Otherwise it’s just an engine and a spare genset, but no domestic batteries, chargers or inverters. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

Post sailing we have a chance to look below decks of the ClubSwan 125 and it’s way more Spartan than I had been expecting. There is some cabin comfort for overnight races and a focus on safety in the saloon for guests. That’s it.

“As you get faster and faster you start to think of the security on board,” Echávarri explains. “We developed a super light, safe interior which is minimalist and nice looking.” The saloon seats rotate over a central hinge to suit the heeling angle and the table cants at multiple angles on titanium hinges. The ‘galley’ is a gimballed microwave on a central bulkhead unit with fridge below (“this is all we allow them,” Echávarri grins). Otherwise it’s just pipe cot-style bunks each side of the saloon and a day heads/shower.

The forepeak is known as the cathedral for its exhibition of bare structures, stringers, bulkheads and longitudinals. Photo: Mark Lloyd / Lloyd Images

The minimalist nature encourages you to focus on the build and finish quality, which is quite remarkable. A closer look at the bulkheads and doors reveals they are all bare carbon. Bar the deckheads and sole panels there are no liners, no panels, not even a drop of paint. It really is a Formula One shell built and finished with Nautor quality.

Move forward from the saloon and you won’t find any of the luxury cabins or accommodation you might expect on a large Swan, just a bare central engine room, the foil casing and acres of the black stuff. See for yourself on our walkthrough video on yachtingworld.com

What’s the goal?

“At the moment the challenges are the races – the Fastnet, the Middle Sea Race,” says Echávarri. “And slowly we will see the real potential. The concept didn’t start with a record breaker brief and we don’t know if it will be faster than Comanche yet. If we feel like it has the potential, we would like the north Atlantic.”

Whether speed is best measured for you on a Moth, SailRocket, an Ultime trimaran or this goliath, those who push for line honours and records will always make headlines. The ClubSwan 125 could potentially set a new bar in that respect. And by taking line honours in its first event, Skorpios has already proved it’s got the necessary sting in its tail.

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams. Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

What Are the Fastest Types of Sailboat (and Why)?

For most of us in our "normal" sailboats, we can get going "fast" on a good breezy day. Even a small day-sailer can give you a white-knuckled ride in the right conditions, and good racers in modest boats can put up double-digit speeds. Twelve knots can feel really fast when you're used to half that. But what does fast mean now, and what are the fastest types of sailboats? And what makes these speed demons fly?

The fastest types of sailboats are:

- Specialized performance boats : 65.45 knots

- Foiling multihulls : 44 knots

- Foiling monohulls : 50 knots

- Windsurfers & kiteboards : 50+ knots

- Racing skiffs :

- Performance multihulls : 20 knots

- Offshore racing monohulls : > 20 knots

As of this writing, the fastest sailboat in the world is a specialized boat called Vestas Sailrocket 2. In 2012 she recorded a sustained speed of 65.45 knots over a 500-meter course in a sanctioned speed record. Other fast sailboats include a variety of foiling monohulls and catamarans, kite surfers, windsurfers, and performance catamarans and trimarans.

Stick around, strap on your crash helmets, and come look into what causes ludicrous speed in today’s modern sailboats. First, we'll explore what makes sailboats fast or slow. Then, we'll explore the fastest sailboat types and their speeds (jump to the list ).

On this page:

What is "fast" for sailboats, what makes a sailboat...not fast, the fastest types of sailboats.

"I feel the need, the need for speed!" Pete "Maverick" Mitchell in Top Gun

Fast is always relative. If you sail a small dinghy, the eight knots that has you white-knuckled and hiking hard barely pegs the fun-meter on a fifty footer racing sled.

But for "Fastest" there are absolutes. The World Sailing Speed Record council keeps records of various sorts as part of the World Sailing organization. They keep records for straight-line speed (500 meters, nautical mile) and many distance records from races and ocean crossings.

What makes up "fast" is also determined by the type of measurement. A kite surfer will put up amazing speed numbers of a mile but can't cross oceans. Some ocean races only allow certain classes of boats - multihulls are often excluded, and ocean race records are recorded by elapsed time and average speed.

To determine "fast" for our list, we're going to look across categories and pull out the best of the best.

To understand why screaming fast boats are fast, it's important to know what these speedsters need to overcome to break out and sail fast.

Power and Weight

If you apply the same amount of force to two objects with different mass, the lighter object will accelerate and move faster. Throw a light plastic ball with the same force as a steel ball the same size, and the plastic ball will fly faster and farther.

With sailing, in the same conditions with the same driving forces (wind and sail area), the lighter boat will sail faster. If you can reduce weight, you can go faster, and racing sailors can be over the top stripping weight to improve performance. It's not just weight in the hull; weight up the mast can hurt a boat’s performance too.

Using modern building materials like carbon fiber and honeycombed cores cuts major weight from hulls. Couple that with multi-hull or foiling designs which eliminate heavy keels, and you get light, fast boats.

Friction, Drag, and Wetted Surface

Although water doesn't feel it, it's rather sticky. On a molecular level, water adds considerable friction when a hull pushes through the water. High-performance yachts have mirror-polished finishes to eliminate drag, but a slick bottom isn't enough to get the insane performance we're looking for.

Friction between materials is governed by how slippery the two surfaces are and the surface area of contact between them. Imagine dragging a piece of plywood flat across a carpeted floor. There's a lot of contact between a 4' x 8' piece of plywood and the carpet: thirty-two square feet. It will be hard to drag lying flat.

Now lift one end of the plywood and drag it. You've cut the surface area from 32 square feet to a few square inches, and the plywood drags easily. The same concept applies to boat hulls - the less hull you have in contact with the water, the less drag to slow you down.

Displacement hull shapes can affect how much area is in the water and will change as the boat heels.

Multihulls can lift a hull out of the water in the right conditions, cutting drag in half.

Hydrofoils aren't a new concept, but recent advances in materials science and yacht design have led to major advances in boat speed. Foiling boats lift the entire hull clear of the water, reducing the wetted area to the foils in contact with the water.

Several production boat companies are experimenting with “foil assisted” monohulls - traditionally ballasted boats with foils to lift them partially out of the water to reduce wetted surface drag. Time will tell if the technology works and the market wants it.

In some of the fastest boats, air drag can also be a factor as speeds get over 20 knots. Streamlining of above-water components takes on new importance.

Sail Area and Force

Bigger sails catch more wind, any sailor knows this. And bigger boats have bigger sails, right? But how can you look at the sails and hull together to make the boat faster?

Yacht designers use the Sail Area to Displacement (SA/D) ratio to categorize boats by performance. Displacement is equivalent to the weight of a boat, so the lighter the boat the lower the displacement.

Calculating sail area to displacement Sail Area to Displacement isn't a straight-line ratio since the impact of displacement isn't linear. It's calculated by dividing the sail area in square feet by the displacement in cubic feet to the 2/3 power. SA/D ratio = sail area (sq ft) / (displacement in cubic feet)^2/3 To get displacement in cubic feet in seawater, divide the weight of the boat by 64 lbs, the weight of a cubic foot of seawater.

The higher the SA/D ratio, the more powered up the boat. By reducing displacement increases the ratio. Kiteboards and windsurfers take this to the extreme, with very low displacement boards for hulls with large amounts of surface area.

Developments in wing sail technology have also increased high-end performance. Sail performance is more about lift than size , and wing sails generate tremendous lift with a trimmable, reduced airfoil profile.

The SA/D ratio goes out the window once a boat foils, since it's only a rough guideline assuming the hull is in the water. Foiling changes all the math.

Sailing Faster than the Wind

For centuries, sailing faster than the wind was as inconceivable as flying. Modern boat designs and foiling technology has changed all that. Once a boat moves at an angle towards the wind, its apparent wind - the wind observed on the sailboat - increases. This generates lift, and a lightweight boat with a lot of sail area can generate enough lift to sail faster than the wind.

Apparent wind is how the wind feels on the boat. It's the true wind added to the wind caused by the motion of the boat. The faster the boat moves, the more forward the wind feels.

Add foils, and all bets are off - the current America's Cup is a stunning display of boats sailing many times the speed of the wind.

The physics explaining this (read on kqed.org ) are beyond this article; the result is the sails generate lift to accelerate the boats past the true wind speed and the boats sail on their own apparent wind.

Very few of the world’s fastest types of boats are commonly available, and most of them are racing focused and seen in those venues. There are some affordable, smaller options, though they take some physical fitness and skill to sail.

Ice boats and land sailers deserve a mention, as they sail on the wind. But they don't float, so we're not putting them with the boats. Water is a lot less sticky when it's frozen, and sailing on blades has gotten speeds over 100 miles per hour. The land speed record for a wheeled land sailer is 126.1 MPH (202.0 KPH).

Specialized Performance Boats

Many of the top sailing speed records have been set by purpose-built boats designed for setting speed records. These are the sailing equivalent of drag racers - purpose designed for speed rather than other competition or use. Two of the best-known are Vestas Sailrocket 2 and Hydroptère .

Hydroptère is a sixty-foot foiling trimaran and set the world speed record in 2009, sustaining 50+ knots over 500 meters and one nautical mile.

Vestas Sailrocket 2 is the current speed record holder over 500 meters with 65.45 knots and holds the nautical mile record with 55.32 knots. Vestas Sailrocket 2 is a trimaran in that she has two hulls (or floats), but the specialized design has a wing sail offset over one while the helmsman sails from a pod on the other hull.

Foiling Multihulls

While the specialty boats are setting records, a variety of foiling multihull boats are raced in sizes from small single-handers up to the AC72's used in the 2013 America's Cup. Boat speeds in the 2013 America's Cup were typically at thirty knots or higher, with speeds hitting 44 knots.

There are many foiling multi classes, including the GC32 and the F50. Even a small foiler like the IFly15 can hit speeds of 25 knots.

Multihulls don't need ballast for stability, so they accelerate to foiling speeds without tipping and stay on the foils with three points of contact usually in the water.

Foiling Monohulls

Foiling dinghies like the Moth woke dinghy sailing up to high foiling speeds. Several single-handed small dinghies are in the market, and sailors have been experimenting with adding foils to existing designs like the Laser and even the Opti to hit double-digit speeds.

Foiling monohulls are trickier than cats since they have only two foils and are less stable. Dinghies use crew weight to keep stability, but larger monohulls have been a problem because of pre-foiling stability without a keel.

The foiling AC75 designs in the 2021 America's Cup solved this with moveable foils, which act as ballast when retracted and foils when in the water. With sophisticated computer feedback systems and skilled sailing, these boats have cracked 50 knots on the racecourse, with in-race speeds in the 30 and 40-knot range when the boats are foiling. These boats can foil in less than ten knots of true wind, hitting speeds three or four times the wind.

Windsurfers & Kiteboards

Drag race speed records are set and broken by windsurfers and kiteboards regularly. The "hull" is a surfboard - a low profile, low displacement hull. Large sail area and low displacement allow speeds over fifty knots in record attempts. Even casual wind and kite surfers sail at high speeds in moderate wind conditions.

Racing Skiffs

Ultra-light hulls with minimal ballast and massive sail area, racing skiffs ranging from 11 to 18 feet are favorite classes down under in Australia and New Zealand. From single handers to crews of four, these ultrafast boats have been pushing the edge of faster than the wind performance for years, and are still some of the fastest small race boats you'll see on Sydney Harbour.

Sailors pushing the edge have added foils to skiffs (of course...), creating more fast entries in the monohull foiling category.

Performance Multihulls

Gunboat and Outremer are two examples of high-performance catamaran brands you can use for something other than racing. These boats use lightweight but tough construction and sleek designs to make bluewater capable cats capable of double-digit sailing speeds in comfort and safety.

They aren't cheap for the average boat owner, but they are fast and comfortable. Cruising at 20 knots isn't a dream.

Offshore Racing Monohulls

Almost all of the records in the big offshore races are still held by the big maxi racing monohulls, and these are still some of the fastest boats in the world. If you follow offshore racing, you’ll know names like Comanche , Wild Oats XI , Rambler , and dozens of others hold line honors records on most of the major ocean races. While specific races like the Volvo Ocean Race or the Vendee Globe don't always make the records books, they sail fast over great distances.

These boats are campaigned by full crews of professional sailors. Design innovations and updates are constant, with new boats built to outpace and outperform. While they don't have the straight-line speeds of the fast foilers and inshore racers, average speeds close to twenty knots over hundreds or thousands of miles of offshore sailing is some serious offshore velocity.

Leave a comment

You may also like, do i need a license to drive a boat (clear info for 50 states).

If you're thinking of getting your boating license, but aren't sure whether you need to get it, this article is for you. Here, I'll go over the requirements for …

How Big Should a Sailboat Be to Sail Around the World?

What is the Average Speed of a Sailboat?

How Much Fuel Does a Sailboat Use?

What Type of Hull Handles Rough Water the Best?

Seattle welcomes world’s best sailors for J/24 international championship

An armada of racing sailboats is a common enough sight on a Seattle summer evening, but the boats heading out from Shilshole Bay Marina in Ballard from Sept. 28 to Oct. 5 aren’t just part of a run-of-the-mill casual race. For the first time, Seattle will host the J/24 World Championship , drawing 56 teams from 11 countries who will test their mettle against the shifty winds and tricky currents of Puget Sound.

Just as crucially, the sailing teams will also test their mettle against each other as they sail north from Shilshole Bay. The 24-foot-long boat is known worldwide for creating a level playing field because boats must be identical to compete. No team has an advantage because of a souped-up sailboat, which means some of the world’s most skilled sailors — former Olympians are known to frequent the J/24 racing circuit — are heading for our local saltwater.

Since 1979, the world championships have cycled through many of the world’s great sailing venues — Annapolis, Md.; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Malmö, Sweden; Sardinia, Italy — except the Emerald City.

And yet, said defending J/24 World champion Keith Whittemore, “We have a fleet that is the envy of many other racing communities around the U.S. and the world.”