BoatNews.com

From Formula Tag to Energy Observer, the many lives of an extraordinary catamaran

When it launched in 2017, Energy Observer was the first clean ship to produce the hydrogen needed for its propulsion. But before that, it was born above all as an ocean racing boat, with a solid track record and famous skippers. Discover the story of Energy Observer, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year.

The largest racing catamaran in 1980

Born in 1983 under the name Formule Tag, the catamaran , now Energy Observer , was built in Quebec for Canadian Mike Birch . This 80-foot Nigel Irens design was, at the time, the largest racing catamaran in the world. Built in Kevlar on Airex foam and carbon, she is 24 m long, weighs less than 10 tons and has a sail area of 440 m2. On board, Mike Birch set the 24-hour sailing distance record in 1984, sailing 512.5 miles.

Winner of the 1994 Jules Verne Trophy

The multihull was bought by Robin Knox-Johnston and Peter Blake in 1993. Renamed Enza New Zealand, the boat was lengthened to 25.90 m. On board, the two sailors set out to beat the Jules Verne Trophy to become the fastest sailors around the world . Setting off on January 30, 1993, they were forced to abandon after colliding with an ONFI south of Cape Town, South Africa. Thanks to the sponsor, the boat is now under construction, and is lengthened by a further 3m to 28m. It was also fitted with a central living area. The two skippers tried again in 1994, setting a new record of 74 days, 22 hours, 17 minutes and 22 seconds, at an average speed of 14.68 knots, after a fierce duel with Olivier de Kersauson's trimaran .

In 1997, British sailor Tracy Edwards bought the boat to take part in the Jules Verne Trophy . She assembled a 100% women's crew on the catamaran , renamed Royal & SunAlliance. She breaks the women's record for the North Atlantic Ocean in 9 days, 11 hours, 21 minutes and 55 seconds, before attempting to break the round-the-world record . She dismasted after 43 days at sea.

The end of his ocean racing career in 2006

Her ocean racing career came to an end at the hands of Tony Bullimore in 2000. Once again, the catamaran , renamed Team Legato, is lengthened to 102 feet - 31 meters - its current length. She also received a new wing mast. The British sailor sets off on The Race, the round-the-world race of the millennium. The yachtsman finished in 5th and last place. In 2005, he took part in the Oryx Quest, a round-the-world race starting and finishing in Qatar. He finished second and last in the overall ranking after more than 60 days at sea. During this race, the navigator set the record for crossing the South Atlantic in 11 days, 10 hours, 22 minutes and 13 seconds. In 2006, the boat was renamed Doha. He attempts to beat the Jules Verne Trophy on board, but has to give up due to mechanical problems.

A new life as an experimental vessel in 2015

After several years of abandonment, the vessel was finally recovered by Victorien Erussard in 2015 to take part in the Energy Observer program. Modified for a 6-year round-the-world voyage, she was grafted with larger hull volumes and a central nacelle molded in racing trimaran shapes, and lost her mast. Its weight increases from 15 to 35 tons. Several architects are involved in this transformation, including Marc Lombard and Marc Van Peteghem.

Energy Observer is initially equipped with vertical wind turbines and covered with solar panels . In 2019, it will also be fitted with small automated wings, each measuring 32 m2, developed by Ayro. Numerous innovations are also installed on board, including a hydrogen chain and variable-pitch propellers. By the time it returns in 2022, Energy Explorer will have covered more than 50,000 nautical miles.

Our Catamarans

Explore our models in a different way thanks to the virtual marina

Efficiency through design

A feel for the sea: sailboats first and foremost

When volume transforms to real space

Innovation as a foundation

- Smart Electric

- Virtual marina

- Experiences

Energy Observer, a true floating laboratory

21 April 2023

Event location

Energy Observer, a source of inspiration and experience for Fountaine Pajot, allowing the development of the first production hydrogen-powered cruising catamaran.

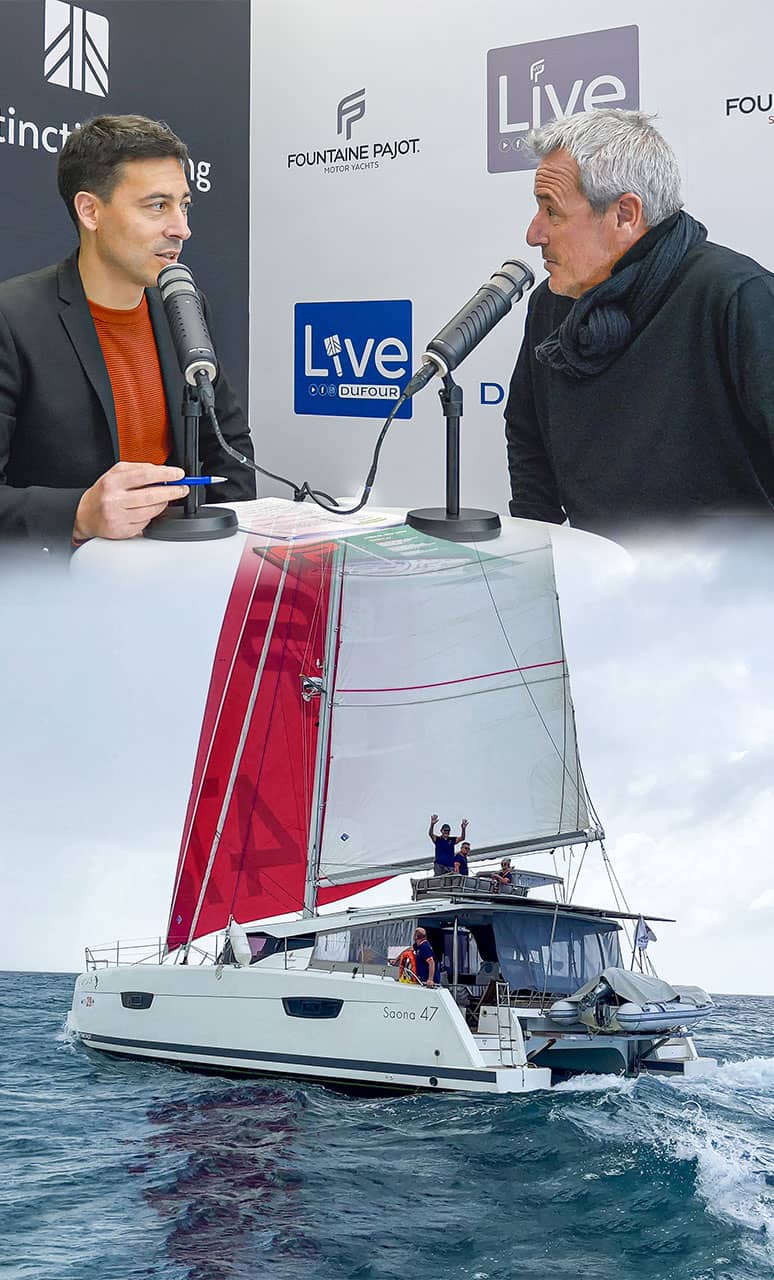

Fountaine Pajot recently collaborated with EODev , a company specialized in hydrogen solutions , to develop its zero-carbon emission boat , the Samana 59 Smart Electric REXH2 . This new generation catamaran, prefiguring the future of boating, has benefited from the technologies developed on board the Energy Observer , catamaran, a true floating laboratory of new energies , which has been sailing the world’s seas for several years. In this new podcast, on the occasion of the partners’ village organized by Fountaine Pajot in La Rochelle, we meet Louis-Noël Viviès , General Manager of Energy Observer, to talk to us about the history of this legendary boat, rich of +40 years of evolution, as well as their experiences and the technical choices they had to make to achieve this project. He also talks about the interest of hydrogen as an energy source and its future in the nautical industry for the next years.

What future for hydrogen in the marine industry? | Energy Observer

Louis Noël Viviès, can you explain and present us what Energy Observer is?

“Energy Observer is one of the first and oldest large racing catamarans. It was originally called “Formule Tag”, the first large catamaran built by Canadair in 1983. So the boat celebrates its 40th birthday in April, which is very interesting from a life cycle analysis perspective. It was famous by Peter Blake, because he beat the round-the-world speed record at the time with this boat. It had 450m² of sail area, and weighed 15 tons. Today, Energy Observer weighs 35 tons, and it has only two small vertical wings on each side of 32m², but they are very efficient.

So it’s very symbolic that the first production cruise boat using these hydrogen propulsion technologies, with the Samana 59 Smart Electric REXH2 , is from Fountaine Pajot . Because it is also here, in La Rochelle, that the famous catamaran “Charente-Maritime” was built, one of the first racing catamarans that made headlines at the time.

So this is the story of a legendary racing boat, which has been modified and lengthened countless times and which is today the first floating laboratory for renewable energies . Today, we are working on new generations of flexible solar panels , on variable pitch propellers and of course on hydrogen …

Indeed, it was a world first to have an electrolyser on a boat, back in 2017, when we launched the boat, which allows us to produce our own hydrogen on board. We have sailed more than 50,000 miles with this technology, the equivalent of two round the world tours. It is a very efficient laboratory with engineers and sailors from the merchant navy on board. It’s really very efficient.”

What are the challenges that Energy Observer had to face to implement a complete hydrogen system on board?

“It was the fact that it was really innovative, there were a lot of standards and regulations to respect. However, as we were really the first, we were quite well followed and accompanied. But very clearly, on the first departures, when we were refueling with hydrogen, with the cables laid directly on the dock by a small truck, it was not easy. We also had a lot of problems with the electrolyser to produce our own hydrogen on board, at the beginning it didn’t work, we must be clear. Today, we still have a lot of work to do on the compression, because yes we use gaseous hydrogen and not liquid, so we have to compress the hydrogen to store it. Indeed, there were no small compressors on board, so we had to design custom-made compression systems.

At each step, we had to innovate, make reliable, break and replace. But on the hydrogen part, since the boat has been equipped with a Toyota fuel cell from the automobile industry, to convert hydrogen into electricity , it is much simpler than with our prototype fuel cell. These fuel cell are subject to strong constraints, such as a marine environment, with humid and salty air, shocks, temperature variations… Not to mention fine particle pollution. It may seem trivial, but there are a lot of diesel boats in the ports, and these fine particles must not be enter the fuel cells, because that would damage the system, so we have worked a lot on air filtration systems. Not to mention the cooling system which is an exchanger using sea water as a cooler…

So everything had to be invented, it was step by step. I salute the enormous work done by the engineers on board, even if the average speed of the boat today is around 5-6 knots with peaks of 12 knots. But when we think back to the first big boat of this type, Planet Solar, a big German boat that was 125 tons and that ran only on solar energy , it only went around the world at an average of 1.8 knots.

Today, after five years, Energy Observer 1 is almost at the end of its development. We are now doing a lot of reliability work, we are trying new generations of solar panels… but of course we are still trying a lot of things in terms of hydrogen, especially everything concerning the corrosion on board.

To be honest, when we launched the boat in 2017, I didn’t think it would work so well, but it works! That’s why today we’re very proud to see production boats adopting these solutions, because we’re convinced that’s really the future, we don’t see any other solution.”

Thanks to the experience you have acquired with Energy Observer, how do you see the future of hydrogen implementation in the maritime industry?

“To be precise, we think that on the “small” boats we will use automobile technologies, for several reasons. First, because it is much cheaper because they are manufactured in large series. You should know that this year (2023-2014) Toyota has a production target of 30,000 units of fuel cells , the same one that is present on Energy Observer and the Samana 59 REXH2 of Fountaine Pajot . So we are no longer working with fragile prototype fuel cells, with a virtually unknown lifespan. We now have a track record, with extremely reliable data on the ageing of the boat and on the corrosion of the membranes. So we have life expectancies that are really becoming compatible with maritime use. Then, I think that we will use more and more these industrial fuel cells because, in addition to being inexpensive, they are very reliable, light and compact. The hydrogen will be stored in a gaseous state, because in the automobile industry it is gaseous, with pressures of up to 700 bars, which is the standard in this sector.

Of course, on very high-powered boats such as super yachts or cargo ships, which are the big projects we are working on today with Air Liquide and CMA CGM, we will switch to liquid hydrogen, cooled to -252 degrees. These are truly innovative technologies. In my opinion, we are back in a cycle of real innovations, breakthroughs and development, as we did at the time for Energy Observer 1.

However, the boundary between gaseous hydrogen , which I would qualify as standard and mass market, and liquid hydrogen , which is the future of heavy maritime transport, will become increasingly porous. We realize that the heavy truck industry is investing a lot in small liquid hydrogen tanks. But there is still a long way because behind it there is not yet the technology to process what is called “vapor lock.” When you cool hydrogen to -252 degrees there is evaporation with a loss of about 10 to 15% per day. So if you have a cargo ship that uses energy continuously, both during its navigation and dock phases, this hydrogen evaporation can be used, of course. But with a sailing boat that will spend 7 days at sea, then after several days or months at dock with nobody on board, it is less coherent to lose 15% of your tank per day. You have to have permanent consumption for it to be interesting, so in my opinion it will be reserved for professional ships, passenger boats or fishing boats. […] ”

Pour synthétiser vos propos, vous imaginez donc l’avenir avec de l’hydrogène liquide pour les navires professionnels et transport maritimes lourds, et de l’hydrogène gazeux pour des bateaux de type croisière comme le Samana 59 REXH2 ? Quand est-il des solutions de recharge ?

« Oui c’est ce que je pense. Après, bien évidemment, aucun de ces bateaux n’a d’intérêt à produire son propre hydrogène à bord, comme nous le faisons. Cela dépend donc surtout du déploiement de stations de recharge à hydrogène dans les ports. Toutefois, de l’hydrogène, il y en a des quantités industrielles partout. Pour faire 1 litre de diesel vous avez besoin de beaucoup d’hydrogène. Le Diesel et l’Essence sont fabriqués à partir de pétrole brut qui est raffiné avec de l’hydrogène. Donc dès que vous avez une raffinerie, vous avez des quantités énormes d’hydrogène.

Le problème, c’est le lien entre ces grosses quantités d’hydrogène liquide (le plus vert et décarboné possible) et comment le faire parvenir aux bateaux. La solution, c’est ce qu’on appelle un “dispenser”. C’est une station qui prend cet hydrogène liquide, le compresse à la bonne température pour qu’il devienne gazeux et stable, pour ensuite l’injecter dans le bateau. Ça ne demande pas beaucoup de place. Ce sont des investissements qui ne sont pas énormes, mais on trouve que le déploiement est long, le temps que les collectivités et les ports s’emparent du sujet. C’est toujours l’histoire de l’œuf ou de la poule, il n’y a pas de consommateur aujourd’hui, ou très peu. C’est pour ça qu’on compte beaucoup sur des gros événements, comme les Jeux Olympiques de 2024 , qui veulent promouvoir l’hydrogène , afin de pouvoir créer une demande un peu soudaine qui justifierait l’investissement. La religion des Jeux Olympiques c’est que chaque investissement ait un usage derrière qui rende pérenne l’investissement, donc on compte sur cet évènement. Mais c’est un peu une bagarre de tous les jours avec à la fois les énergéticiens, qui investissent dans ces systèmes et puis avec les collectivités locales, qui aujourd’hui voit encore un peu l’hydrogène comme quelque chose de futuriste, alors que ça ne l’est pas du tout ! […]

En clair, tout ceci, c’est du concret. Et surtout ça a un usage direct et immédiat pour plein d’applications, comme avec le Samana 59 REXH2 , par exemple. Donc nous sommes très heureux, on a la sensation qu’on a la même culture, qu’on a la même approche, qu’on est hyper pragmatique. […] »

Louis-Noël Viviès, Directeur Général d’Energy Observer.

You may also be interested in

Interview with an Alégria 67 Owner & guided tour

Xavier Embroise

Alégria 67 Owner

How does Smart Electric technology work? Answer on video…

Smart Electric: a complete overview of this technology, its origins, how it works and its everyday benefits... #Broadcast

Acquire a flagship catamaran, tailor-made solutions: charter management, customization…

How do you buy a flagship? What types of ownership are there? How do I get proper support? Find out all you need to know in this broadcast...

What is the future of hydrogen in recreational boating?

Discover the challenges of implementing Hydrogen, thanks to our experts...

Isla 40 and Astrea 42, the perfect models for starting out in the world of catamarans?

Isla 40 and Astréa 42, find out all about these catamarans through two testimonials...

The Tanna 47, a multi-purpose boat that ticks all the boxes?

Tanna 47: a program to find out all about this model...

Posidonia seagrass beds, the blue lung of the Mediterranean sea? WWF explains us everything

The first 100% electric hydrogen catamaran

The Samana 59 REXH2, a hydrogen catamaran forerunner of future 100% carbon-free solutions.

How Garmin envisions the future of its navigation equipment?

Garmin has been an official partner of Fountaine Pajot for many years, equipping Fountaine Pajot sailing catamarans and motor yachts with navigation equipment and interfaces.

Rallye “des Îles du Soleil”, a friendly and safe transatlantic race?

Pierrick Garenne comes back on this new edition of the Rallye des îles du Soleil.

Aura 51 Smart Electric: behind the scenes of its conception

1 year later, where is Fountaine Pajot’s environmental strategy?

Subscribe to the newsletter

Follow the adventures of Fountaine Pajot Owners, discover the latest news and upcoming events, and take part in the development of the Boat of tomorrow!

Compare models

Catamaran New 41

Catamaran Astréa 42

Hosting capacity

Motorisation

Technical information

User-friendly areas

Sunbathing Oui

Kitchen Non

Discover the prices

Double rooms

Your contact details

One last step before reaching the next page & discovering the prices proposed & main options for this version! You'll then be able, to schedule a live chat with your local dealer to discuss all the options and configurations available for this model!

Your home port

Any questions?

No pack information currently available online for this Flagship model. We will get back to you directly. Thank you

Would you like to configure this model’s options or set up another model?

Make an appointment with your nearest dealer and choose the boat of your dreams.

- The Odyssey

- The Innovations

Nigel Irens: It's a pleasure to see the new life of the boat

- Renewable energies

- On-board Technologies

Francis Joyon, Ellen MacArthur and before them, Mike Birch, winner of the first Route du Rhum and Sir Peter Black, Enza, have put their trust in Nigel Irens to design their record-chasing engines. Energy Observer came off the naval architect’s drawing board in 1983 under the name of Formule TAG. Lengthened and transformed into an experimental vessel, the 30-meter catamaran today explores the planet. Meeting with its architect.

On the pontoons of the Route du Rhum, a spry person in his sixties is casting his astute eye over the vessels moored in Vauban Marina. The British naval architect Nigel Irens is the father of quite a few of them. But it’s certainly Energy Observer which has held his attention the most. In 1983, Formule TAG was the world’s biggest record-chaser.

Formula TAG

Lengthened and modified, Energy Observer now explores the planet with Victorien Erussard at the helm. The opportunity for a passionate discussion in the cockpit, version V2, of a vessel which only continues to increase the experience.

Energy Observer

In 1982, when Mike Birch contacted you to design his new vessel, what were his specifications?

It was a time when catamarans dominated, with Loïc Caradec’s Royale II, Marc Pajot’s Elf Aquitaine or Charente Maritime skippered by a group of friends led by Jean-François Fountaine. Formule TAG (editor’s note: the original name of Energy Observer) had to be, with its 80 feet (24.37 meters), the largest catamaran of its time.

What was the vessel’s program?

Mainly crewed races but also record attempts.

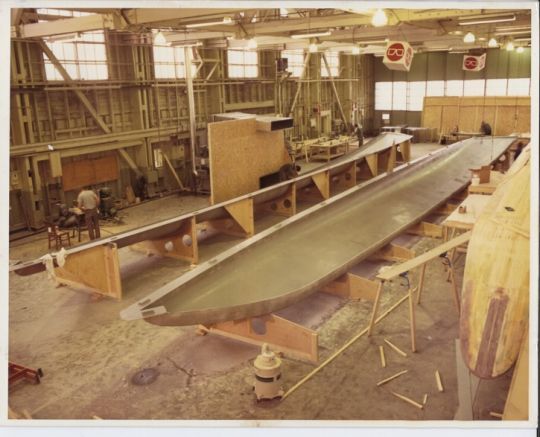

You designed it, the work was coordinated with the architectural firm Huot and Dupuis, but where was it built?

It was built in Montreal (Canada) by the aviation company Canadair, the property of TAG the sponsor. The most notable change was the size. Nobody had ever made such a big vessel.

Has the catamaran therefore benefited from the technology of the aviation industry?

This was a real opportunity. It’s the first racing vessel to have benefited from aviation standards with Kevlar material (pre-preg of resin (prepeg). At the time, it was the world’s second largest composite object… just after the doors of the space shuttle!

Why choose Kevlar?

Kevlar was available in larger quantities than carbon in the 1980s. It then became outdated because it had very good mechanical qualities in traction but a lot less in compression since its adhesion between resin and fibers is not very good. All the planks were made of Kevlar. Carbon was used for the deck edge (editor’s note: deck and hull junction line). The same for the arm parts where there was a lot of compression. The challenge was to adapt this standard aerospace technology, which used autoclaves, to our requirements where we were unable to use autoclaves due to the size of our parts. We did a lot of testing with the help of Canadair personnel.

Were there any anecdotes during construction?

Assembling was done in a shed in Quebec in a public area that was open to the public, as part of the 400th anniversary celebrations of Malouin Jacques Cartier’s discovery of Canada. It was sometimes a bit surreal when we were working at night to the sound of an orchestra. We also learned six weeks before its inauguration that the vessel was going to sail on the day of its launch with Pierre Elliot Trudeau, Canadian Prime Minister, on board. It was tight in terms of organization. We strengthened the teams and worked day and night. On launch day, a turnbuckle (editor’s note: a device which holds the cables) was defective. We have anyhow sailed under reduced sails with “do-it-yourself” workmanship!

The fact that the vessel is today a new life, is this important for you?

It’s very important! After 35 years and the different lives that this vessel has had, it’s great to see it continuing. Especially in this context of choosing to recycle a vessel rather than building a new one is a good example.

What are your thoughts on the vessel’s transformation and changes?

The load on the structure in this new configuration (editor’s note: the pod in which the crew lives) doesn’t pose any structural problem to the hulls. It doesn’t risk anything compared to what happens to a vessel whose hulls are loaded by sail plan efforts. The loads are minimal compared to what it has endured during its different world tours. The vessel is in refuge! A great refuge for a great project. I’m very impressed with the quality of the transformation.

- AMERICA'S CUP

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

Energy Observer, the legendary catamaran, celebrates her 40th anniversary

Related Articles

- Allures yachting

- Garcia yachts

- Dufour yachts

- Fountaine Pajot Sailing Catamarans

- Outremer catamarans

- Catana catamarans

- Garcia Explocat

- Dufour catamarans

- Aventura catamarans

- NEEL Trimarans

- Allures Sailing Catamarans

- Fountaine Pajot Motor Yachts

- Garcia trawler

- Beneteau Motorboats

- Aventura Power Catamarans

- Yacht school

Energy Observer: Was an ocean racer, became a technological marvel

François Treguet talks about the Energy Observer, a former ocean-going racing catamaran turned into a "zero emissions" science platform.

Few boats have had such a rich and varied history in the past 40 years as this one, now known as the Energy Observer.

Would Nigel Ayrens and Mike Birch, the boat's creators, recognize her today? The narrow noses of the Formule TAG, now the Energy Observer, remain the hallmark of this famous ocean yacht, but much more has changed over the years.

In 1983, the 80-foot Formule TAG was launched as part of a revolutionary new generation of multihull boats designed for ocean racing and record breaking.

At that time, it was the largest ocean racing catamaran of its kind built using aerospace technology. The following year, he broke the 24-hour race record with 512.5 miles.

In 1993, it was bought by Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston to try to win the Jules Verne Trophy, famed for a spinnaker decorated with bright red and green apples called ENZA (Eat New Zealand Apples).

The second attempt, in 1994, was crowned with success, and the ship set a record for circumnavigation with a crew - 74 days.

The next was Royal & SunAlliance, skippered by Tracy Edwards. Although Jules Verne's trophy proved elusive, Edwards and her team broke seven world records.

Then Tony Bullimore took over, lengthening the yacht's hull to 100 feet and running under the name Team Legato in Bruno Peyron's 2000 round the world race: The Race.

In 2010, it capsized at Cape Finistère in a 15-knot wind. Many believed that the boat would never recover from such an accident: too old for racing, too damaged to be repaired.

However, French entrepreneur Victorien Heroussard, who has sailed everything from Hobie cats and Formula 18 to Route du Rhum and Transat Jacques Vabre, had a different idea.

His goal was to build the first self-sufficient vessel on the 100%. The chassis of the former ocean racing catamaran was the ideal platform, and the rework of the existing boat perfectly matched the project's ambitions.

Since the launch of the Energy Observer in 2012, the project has been under continuous development and has traveled over 30,000 miles to date.

The Energy Observer team believes that for a vessel to become a truly zero-emission boat, capable of sailing from the Arctic Circle to the equator, it needs a combination of energy sources.

“The variety of sources increases reliability, productivity and safety,” says Louis-Noelle Vivies, general manager of the project.

The main driving force on board is provided by two 45 kW electric motors. They are impressive in size and are not used at maximum power, therefore they provide high efficiency.

Choosing a single battery capable of powering them for a long period of time without recharging would lead to a reduction in the weight of the project. Instead, the Energy Observer uses two small battery packs with a total capacity of 100 kW, which is also safer.

The weight of this hybrid solution is still 1.4 tonnes.

In the future, thanks to the development of lighter batteries, this weight should be halved for the same power.

Batteries act as a buffer between the motors and the four different energy sources needed to provide a 24/7 power supply. The most innovative of these is undoubtedly hydrogen.

The battery was developed by project partner Toyota, based on the battery used in their hydrogen-powered Mirai.

“It delivers 10 times more power for the same weight than other batteries on board,” says Vivies. “There are two hydrogen batteries, one in each case, with a peak power of 80 kW.”

Although they are now three times cheaper than the original first generation batteries, hydrogen batteries are still twice as expensive as a generator of the same capacity.

On the other hand, they are guaranteed for 80,000 hours, do not require maintenance and have no associated fuel costs, as the Energy Observer produces (by desalination, purification and electrolysis) and stores in eight tanks of 64 kg of its own hydrogen from seawater.

The battery efficiency is 2.5 times higher than that of diesel fuel when you consider the energy required to extract, process and transport it to the pump.

The battery also generates 50% of heat used on board, so the crew never ran out of hot water and could enjoy a cozy warm interior as they cruise north to Svalbard.

The third source of energy is solar panels, which occupy an area of 202 m² and generate a total power of 35 kW.

Solar panels use different technologies depending on their location on the deck or superstructure.

Some are double-sided to catch rays reflected from the surface of the water. Elsewhere they are coated with a non-slip polymer that improves performance when the sun is not at its zenith.

Wind power is an area that has undergone significant changes since the launch of the Energy Observer.

After experimenting with vertical wind turbines and a traction wing, the catamaran now carries two Oceanwings, a 32 m² rigid wing designed by VPLP and inspired by the America's Cup experience.

Ocean Wings were designed with the ultimate goal of making maritime transport less polluting, and the Energy Observer is an ideal experimental platform for developing this system.

Almost twice as efficient as traditional sails, the wings can be used to both increase speed and reduce energy consumption in addition to electric motors.

The wings also allow the Energy Observer to use a fourth source of power generation - hydroelectricity from propellers in good winds.

The base platform of the Formule TAG hull was lightweight, only 15 tons. Although the catamaran no longer carries its original installation, additional batteries, motors, etc. increased the final displacement to 30 tons.

Therefore, it was necessary to increase the buoyancy of the hull, which was achieved by imposing a second skin, adding volume below the waterline.

In addition to adapting all of these new technologies to a corrosive marine environment, the Energy Observer team's expertise is in finely managing these various energies by optimizing efficiency.

The choice of the most efficient method of propelling or generating electricity occurs at any given moment, before fine tuning the wings or the pitch of the propellers.

Any innovation often makes a big leap from theory to practice, but this project creates data to prove concepts.

The Energy Observer has been traveling the world's oceans since 2017.

In March 2020, he embarked on a journey to attend the Tokyo Olympics and Dubai World Exhibition in 2021, then return to Paris for the 2024 Olympics.

Over the 2,134 miles traveled on the current voyage, the vessel averaged 6.34 knots, with 83% of power generated for propulsion or navigation and only 17% for residential systems used by the five-member crew on board.

Over the past eight months, solar has accounted for 56% onboard production, hydrogen for 7%, and Oceanwings for 37% of the equivalent consumption of the engines saved.

Hydropower has been little used in intertropical latitudes, but it is expected to be used more frequently in more windy regions.

Energy Observer Specifications:

Length: 30.50m - 100ft 0in,

Width: 12.80m - 42ft 0in,

Draft: 2.10m - 6ft 11in

Displacement: 30 tons,

Sail area: 64m² - 700ft², Designer: Nigel Ayren

News and articles

Despite the difficulties, the industry continues its work and steadily delivers new products. Today we will talk about as many as three new products that are worth paying attention to. Interparus understands!

What are the basics of safety rules that parents need to know and how to prepare for a cruise - we tell you the most important things about yachting with children!

Philippe Briand and Jeanneau shipyard have announced their latest development, the 44ft Sun Odyssey 440 cruising yacht.

The New Order: Last Days of Europe Wiki

Attention everyone, The New Order: Last Days of Europe Wiki on Fandom is no longer used, except for TNO Styled GFX Icons . The new wiki is located at https://tno.wiki.gg/ and please claim your old username (with contributions) at https://tno.wiki.gg/wiki/Special:ClaimExternalAccount/ .

National spirits

| How foolish these plans were. |

| But did its people do so too? |

| Political Power Gain: Either their days and numbered - or ours. |

| Stability: Few could ever escape this prison - but one man certainly will try. |

| Cabinet member | Role | Ideology | Trait(s) and effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head of government | Template:Utterly Corrupt | ||

| Foreign minister | Template:Great Compromiser | ||

| Economy minister | Balanced Budget Economy: | ||

| Security minister | Template:Old Prussian |

Moskowien is a Reichskommissariat of the Greater Germanic Reich and as a result is in the Unity Pakt.

| • Nations as of January 1st, 1962 | |

| Americas | • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • |

|---|---|

| Europe | • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • |

| Africa | • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • |

| Middle East | • • • • • • • • |

| Central Asia | • • • • • • • |

| Siberia | • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • |

| East Asia | • • • • • • • |

| South Asia | • • • • |

| Southeast Asia & Oceania | • • • • • • • • • |

| Antarctica | • • • • • |

- 1 SS State of Burgundy

- 2 TNO Styled GFX Icons

- 3 Joseph Stalin

Moscow Mule

Liquor.com has been serving drinks enthusiasts and industry professionals since 2009. Our writers are some of the most respected in the industry, and our recipes are contributed by bartenders who form a veritable "Who's Who" of the cocktail world.

The Moscow Mule is a classic combination of vodka, ginger beer, and lime. Known for it's iconic copper mug, the drink's enduring popularity has left it as a mainstay in bars since the mid-20th century. Despite its name, the Moscow Mule was actually invented in Los Angeles as part of an early stateside marketing push for vodka, and the drink itself is considered an example of the Buck family of drinks—those that include a spirit with citrus and ginger beer.

The History of the Moscow Mule

The Moscow Mule is a mid-century classic that was born in 1941 and helped contribute to vodka’s rise in America. As the legend goes , it was concocted by two men. John Martin needed to sell Smirnoff vodka, a new and generally unknown spirit during the middle of the 20th century that his distribution company had recently purchased. Another man, bar owner Jack Morgan, wanted to deplete the stash of ginger beer taking up space at his Cock ‘n’ Bull pub. They decided to combine the two ingredients with a little lime, and the rest is history. (Though there is a conflicting origin story that says that a bartender by the name of Wes Price was the true originator of the cocktail’s recipe.)

The origin of the Moscow Mule mug is slightly less clear, though evidence points to the connection originating with a Russian woman named Sophie Berezinski, who's father owned copper factory called Moscow Copper Co. Allegedly, poor sales in their home country left the younger Berezinski to travel to the U.S. to find new buyers.

As historian David Wondrich observes, the copper mugs reached Cock 'n' Bull and were used to create a visually distinct presentation for the new cocktail, helped along by Martin who took Polaroid instant photos (then a recent invention) of Los Angeles bartenders and guests holding the copper mugs alongside bottles of Smirnoff. The photos were displayed throughout the bar and given to patrons to share, almost in the same vein as modern social media influencers. As the photos proliferated throughout the Los Angeles cocktail community, it helped to spur demand for the novel drink.

Regardless of how the drink was invented, the easygoing combination of vodka, spicy ginger and tart lime—all packaged neatly in an eye-catching mug—was a hit. More than a quarter century later, the Moscow Mule remains a star. It has even spawned variations, like the Mezcal Mule with mezcal and the Kentucky Mule with bourbon.

Why the Moscow Mule Works

The simple cocktail combines vodka with ginger beer and fresh lime juice. It’s a no-tools-required drink that is built right in that shiny copper mug. Of course, while said mug is always preferred for serving, it’s not essential and shouldn’t deter you from making a Moscow Mule. The drink tastes great no matter the receptacle. So if a highball glass or rocks glass is all you have on hand, don’t fret.

Any preferred vodka will work nicely in the mule, but high-quality ginger beer is a must. You want a top-notch option that and offers enough of a spicy bite to complement the liquor and lime. And keep that bottle cold before you employ it your Moscow Mule. Cold keeps the bubbles brisk and helps stall dilution when you mix all the drink’s ingredients.

This recipe brings the legendary drink up to date while remaining true to its refreshing roots. At its core, the Moscow Mule is deceptively simple and incredibly easy to mix, perfect for any season.

Liquor.com / Tim Nusog

Ingredients

2 ounces vodka

1/2 ounce lime juice , freshly squeezed

3 ounces ginger beer , chilled

Garnish: lime wheel

Fill a Moscow Mule mug (or highball glass) with ice, then add the vodka and lime juice.

Top with the ginger beer.

Garnish with a lime wheel.

What If I Don’t Have a Copper Mug?

No doubt about it: The textured copper mug is a gorgeous part of a classic Moscow Mule. Truth is, it’s less the copper that matters than the conductivity of copper as a type of metal. So, blasphemous as it may appear, a Julep cup—or any other metal container—is a delightful substitute. Because you’ll still get that frosty, deeply cold result.

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Catamaran Sailing Techniques Part 3: Anchoring and picking up a mooring – with Nigel Irens

- Matthew Sheahan

- February 17, 2016

Catamarans can be a bit frisky at anchor, but multihull expert Nigel Irens has some tips to make anchoring and mooring safer and more comfortable

The general game plan in anchoring on a cat under power is much as it is on a monohull – approach the spot where you intend to drop the anchor from dead downwind and signal to the foredeck when you are ready for it to be dropped.

The only snag is the catamaran’s stubborn desire not to remain in a stable condition head-to-wind in anything but the lightest breeze. It’s just as well, then, that the twin engines allow you to hold station and heading reasonably well, provided you’re firm with the controls and act with as much deliberation as you can muster.

It obviously helps if you can avoid hanging around too long in limbo with no way on – which invites that headwind to take control of the boat.

Keeping your position

Once the anchor is on the bottom you can drop back downwind – once again playing the engine controls to help the boat stay head to wind until the point where you have snubbed the anchor in.

If you’re operating in waters that are free from tidal movement or other currents you might expect to lie head to wind like the other boats around you, but there’s another snag that needs to be addressed before you can feel relaxed about this. The problem is related to the above-mentioned reluctance of a catamaran to lie head to wind, although with any luck your boat will already be fitted with a solution to this one.

What happens is that the boat starts to range around the anchor. This process begins as the bow falls off to one side or the other and the boat starts to ‘sail’ forward – say at about 45° to the wind axis. Eventually the bow will be forced to come head to wind because the direction of travel can only be a radius around the anchor.

Eventually the boat slows down and comes to wind, but because the anchor rode is still pulling the bow to one side the boat tacks through the eye of the wind and sets off with renewed vigour on the other tack.

It’s not hard to imagine that this cyclic pattern can repeat itself until the boat is careering about, taking up much too much space in the anchorage and generally winding up the neighbours. Viewed from above the physics of this phenomenon is not unlike that which makes a flag flap.

The bridle takes the load and the anchor chain to the boat is now slack. Note recovery line

To solve the problem the anchor rode needs to be attached to a bridle rather than directly to the bow roller. This involves attaching one end of a rope to each bow and the middle of the resulting span to the anchor chain or warp. As the bow of the boat falls off the wind axis the tendency is for the rope on the lee bow to take the load as the windward one goes slack.

This asymmetric load will be far more effective in putting the boat back head to wind before it has had time to build up any speed than a single rode to the centreline.

Anchor sequence

You can experiment with the length of the bridle, but something approaching an equilateral triangle (as viewed from above) seems to work pretty well, although the boat you’re sailing probably has the bridle already set up correctly and ready to use.

Clear hand signals are also required when raising the anchor to help the helmsman reduce load on the windlass

So the sequence of events in anchoring is roughly as follows:

- Pick the best looking spot to anchor

- Approach the chosen spot from downwind and give the crew the go-ahead to drop the anchor when you’re in position.

- Move astern downwind as the crew pay out the anchor rode and snub the anchor in.

- Set the bridle and slacken the anchor rode until the load is taken up by the bridle.

- If the boat won’t settle at her anchor for some reason – fickle winds, some unwanted counter current or whatever – you may have to think about laying a second anchor.

This is best done from the tender and although the learning curve might be quite steep, a bit of trial and error could leave you better placed for the day you need to ride out heavy weather from a known direction.

The second anchor should be set so that the angle between the first and second anchor chain is between 90° and 60°.

Picking up a mooring

If you are picking up a mooring rather than anchoring, visibility – or the lack of it – might be a problem, so the old tactic of getting a crewmember to hold the boathook aloft from the forward end of the boat and point it at the buoy is as good a way as any of telling the helmsman what’s happening.

If the buoy you’re aiming to pick up has no rope or chain leader attached to it then it might be almost impossible to get a temporary line through the ring without launching the tender – especially if your freeboard is high. If so there’s a cheeky work-around involving offering the boat up to the mooring stern first.

Using a boat hook to help guide the helmsman to the buoy that you want to pick up. Don’t worry about looking like a whaler about to launch a harpoon!

For a start the helmsman should have both a good view of the buoy and the ability to communicate with the line handler. Once a line has been attached, the helmsman should be able to spin the boat round easily enough so the line handler can to bring a slack mooring line round to the bow as the boat turns – but not so slack as to risk it getting sucked in by the propeller, which could be embarrassing at best and dangerous at worst.

Mooring sequence

A recap on the procedure would read something like this:

- Find the buoy you have been allotted – or choose a suitable one if you haven’t had any specific instructions.

- Bring the boat up to it from downwind and get the crew to bring up the leader with the boat hook, get a temporary line through the eye and secure the free end on a cleat or any other strong point that comes to hand.

- That’s it – you’re safe! It just remains to set the bridle as above and you’re done.

Anchoring or picking up a mooring under sail is more difficult than would be the case in a monohull. This results from that old problem about catamarans being more skittish than monohulls, having more windage above the water and less hull below it.

That is not to say that it couldn’t be attempted when an anchorage is spacious enough and not overcrowded. On the contrary, taking on such challenges in the right conditions helps build confidence and develop the skills necessary to anticipate the way the boat will behave in different circumstances.

Ultimately much of the pleasure that sailing has to offer involves mastering new skills and developing prowess in handing whatever boat you happen to be sailing.

Inevitably doing so involves taking on challenges that will get your adrenalin popping from time to time – as it is meant to do. It was ever thus!

Do’s and don’ts

- DO spend some time practising holding your catamaran head to wind under power.

- DO snub the anchor in properly so that you can feel the boat being tugged forward when you put the engine back in neutral.

- DO make sure your crew are properly briefed about their role in making anchoring and mooring a pleasure.

- DON’T forget to make sure they know they should delay paying out more chain after the anchor has hit the bottom until the boat is visibly moving astern. This avoids the risk of chain piling up on top of the anchor and perhaps fouling the flukes.

- DON’T drop an anchor if there really isn’t enough space. A catamaran needs more space than other boats because it is big and often a bit frisky at anchor.

- DON’T give up too easily – you have an ace card to play in that you draw less than the average monohull so can probably find some clear water that’s no use to them! In tidal waters you can even dry out and have a very peaceful night.

Our eight-part Catamaran Sailing Skills series by Nigel Irens, in association with Pantaenius , is essential reading for anyone considering a catamaran after being more familiar with handling a monohull.

Part 4: Cruising upwind under sail – potentially a cat’s weakest point of sail

Series author: Nigel Irens

One name stands out when you think of multihull design: the British designer Nigel Irens.

His career began when he studied Boatyard Management at what is now Solent University before opening a sailing school in Bristol and later moving to a multihull yard. He and a friend, Mark Pridie, won their class in the 1978 Round Britain race in a salvaged Dick Newick-designed 31-footer. Later, in 1985, he won the Round Britain Race with Tony Bullimore with whom he was jointly awarded Yachtsman of the Year.

His first major design success came in 1984 when his 80ft LOA catamaran Formule Tag set a new 24-hour run, clocking 518 miles. During the 1990s it was his designs that were dominant on the racecourse: Mike Birch’s Fujicolour , Philippe Poupon’s Fleury Michon VIII , Tony Bullimore’s Apricot . Most famous of all was Ellen MacArthur’s 75ft trimaran B&Q, which beat the solo round the world record in 2005.

His designs have included cruising and racing boats, powerboats and monohulls, but it is multis he is best known for.

See the full series here

A special thanks to The Moorings, which supplied a 4800 cat out of their base in Tortola, BVI. www.moorings.com

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Originally named Formule Tag, this maxi-catamaran was built by Canadair in Québec, Canada in 1983, under the supervision of Canadian skipper Mike Birch and British designer Nigel Irens. The yacht was built to compete in the inaugural Transat Québec-Saint-Malo—a trans-North Atlantic sailing race celebrating Jacques Cartier's 1534 voyage from Saint-Malo, France, to present day Québec City.

The largest racing catamaran in 1980 . Born in 1983 under the name Formule Tag, the catamaran, now Energy Observer, was built in Quebec for Canadian Mike Birch.This 80-foot Nigel Irens design was, at the time, the largest racing catamaran in the world. Built in Kevlar on Airex foam and carbon, she is 24 m long, weighs less than 10 tons and has a sail area of 440 m2.

In between IT82 and Apricot, Irens designed what was then the world's longest racing catamaran—the 80-foot carbon fiber/Kevlar Formule Tag, built for Canadian Mike Birch in Montreal. Tag was built by Canadair using aerospace technology. The largest ever pre-preg structures were "cooked" in giant ovens.

The basic Formule TAG hull platform was light, at just 15 tonnes. Although the catamaran no longer carries its original rig, the additional batteries, motors etc increased the final displacement ...

Built in Canada in 1983 by the naval architect Nigel Irens, under the supervision of the sailor Mike Birch, she was christened "Formule Tag". In 1993, with Sir Peter Blake, the boat became "ENZA NEW ZEALAND" and won the Jules Verne Trophy, securing a round the world sailing record under sail of 74 days, 22 hours, 17 minutes and 22 seconds.

"Energy Observer is one of the first and oldest large racing catamarans. It was originally called "Formule Tag", the first large catamaran built by Canadair in 1983. So the boat celebrates its 40th birthday in April, which is very interesting from a life cycle analysis perspective. It was famous by Peter Blake, because he beat the round ...

It was a time when catamarans dominated, with Loïc Caradec's Royale II, Marc Pajot's Elf Aquitaine or Charente Maritime skippered by a group of friends led by Jean-François Fountaine. Formule TAG (editor's note: the original name of Energy Observer) had to be, with its 80 feet (24.37 meters), the largest catamaran of its time.

Formula Tag. Formula Tag was a 74-foot waterline length catamaran that was sailed across the Atlantic Ocean in 1984. [1]

Energy Observer, the legendary catamaran, celebrates her 40th anniversary by Energy Observer 19 Apr 2023 05:28 PDT ... Built by Canadair in Canada in 1983, the famous aircraft manufacturer, under the name of Formule TAG, Energy Observer has had a prestigious lineage of skippers. The first winner of the Route du Rhum, Mike Birch, was the pilot ...

In 1983, the 80-foot Formule TAG was launched as part of a revolutionary new generation of multihull boats designed for ocean racing and record breaking. At that time, it was the largest ocean racing catamaran of its kind built using aerospace technology. The following year, he broke the 24-hour race record with 512.5 miles.

Originally the Nigel Irens designed catamaran "Tag" built in Canada in 1984. Bought late 1992 and re-modelled she became Enza. Skipperd by RKJ and Peter Blake, she attempted to beat 80 days around the world in 1993 but struck an object in the Southern Ocean and withdrew. ... For that reaston Formule TAG's decks have specially designed round ...

Formule Tag est un catamaran de course au large construit en 1983, qui a participé à de nombreuses courses à la voile. À partir de 2015, il est transformé en navire expérimental propulsé par éoliennes et l'hydrogène produit à bord ; il est rebaptisé Energy Observer pour ce nouvel usage.

His first major design success came in 1984 when his 80ft LOA catamaran Formule Tag set a new 24-hour run, clocking 518 miles. During the 1990s it was his designs that were dominant on the ...

His first major design success came in 1984 when his 80ft LOA catamaran Formule Tag set a new 24-hour run, clocking 518 miles. During the 1990s it was his designs that were dominant on the ...

It wasn't until the age of the maxi-multis that the 24-Hour Record changed hands again, first going to the 100ft catamaran Formule Tag in 1983 with an average speed of 21.3 knots—under 2 knots faster than the 250ft clipper. Over the next decade, a number of French campaigns would chip away at the record, only ever improving it by a matter ...

His first major design success came in 1984 when his 80ft LOA catamaran Formule Tag set a new 24-hour run, clocking 518 miles. During the 1990s it was his designs that were dominant on the ...

PRECALCULATED D-PN HANDICAPS CENTERBOARD CLASSES Cape Dory 14 Centerboard CD-14 (125.40) [124.2] Caprice

Blini (блины) - Russian pancakes, can be eaten both as a dessert with jam or with meat filling. Borsch (борщ) - red beetroot soup with sour cream. Pelmeni (пельмени) - Russian dumplings. Solyanka (Солянка) - a little bit of everything in the soup - pickles, lemons, olives, sausages.

Tag. MCW. Language(s) German (official), Russian (unofficial) Capital. Moskau (Moscow/Москва) Government/party. Kasche Government - National Socialist German Workers' Party. Ideology. National Socialism. Faction. Einheitspakt (as an Autonomous Reichskommissariat) Head of state.

His first major design success came in 1984 when his 80ft LOA catamaran Formule Tag set a new 24-hour run, clocking 518 miles. During the 1990s it was his designs that were dominant on the ...

Fill a Moscow Mule mug (or highball glass) with ice, then add the vodka and lime juice. Top with the ginger beer. Garnish with a lime wheel. What If I Don't Have a Copper Mug? No doubt about it: The textured copper mug is a gorgeous part of a classic Moscow Mule.

His first major design success came in 1984 when his 80ft LOA catamaran Formule Tag set a new 24-hour run, clocking 518 miles. During the 1990s it was his designs that were dominant on the ...