- Privacy Policy

- Copyright and DMCA Notice

Death on the High Seas: The 1979 Fastnet Race

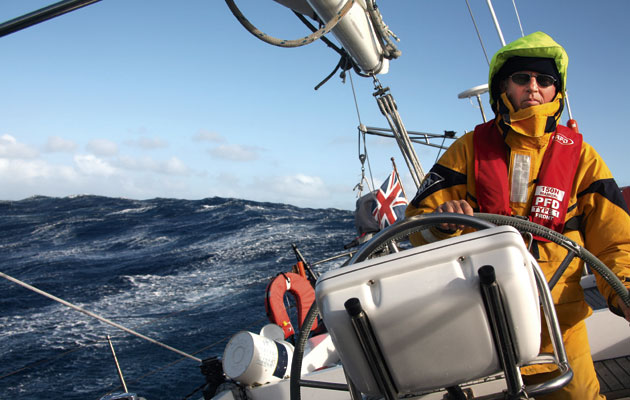

Offshore sailing is one of the most challenging and exhilarating sports in the world, demanding skill, stamina, and courage from those who take part. For sailors, there is nothing quite like the feeling of being out on the open sea, with nothing but the wind and the waves to guide you.

But while offshore sailing can be a thrilling and rewarding experience, it is also one of the most dangerous, with sailors facing a range of hazards that can put their lives at risk. One of the most notorious incidents in the history of offshore sailing is the 1979 Fastnet Race disaster, a tragedy that shocked the sailing world and led to significant changes in the sport.

The Royal Ocean Racing Club’s Fastnet Race is usually held every two years. It’s been that way since 1925 and has always been held on the same 605 miles course.

Sailors set out from Cowes, an English Seaport on the Isle of Wight, and head to Fastnet Rock in the Atlantic , south of Ireland . They then back to Plymouth via the Isles of Scilly. It’s a famed test of some of the best sailors in the world.

The 1979 Fastnet race is notorious for something different though. On August 11, 1979, a storm with hurricane-force winds hit the yachts competing in the race, causing chaos and devastation.

75 boats capsized, 5 sank and 15 sailors lost their lives. Of the 303 yachts that started the race, only 86 finished. It was one of the deadliest yacht races in history and the events that unfolded that day shocked the sailing world to its very core.

A Dangerous Game

We often forget that mother nature is a harsh mistress. The disaster which occurred during the 1979 Fastnet race was caused by an extremely powerful storm that hit the boats as they were crossing the Irish Sea. Meteorologists hadn’t seen the scale of the storm coming, meaning even the most seasoned sailors competing were caught off guard.

- Donald Crowhurst and his Fatal Race Round the World

- What Happened to The Zebrina? Ghost Ship of the Great War

The storm came about due to the collision of a cold front with warm air from the Gulf Stream. This created a rapidly intensifying low-pressure system that generated hurricane-force winds and giant waves. The yacht crews were forced to do battle with winds of up to 70 knots (130km/h) and waves that reached 30 feet (9 meters).

This situation was further worsened by the design philosophy of the competing boats. Many crews emphasized speed over structural strength, taking advantage of new advances in fiberglass to build faster boats. But these new designs were untested in heavy seas, and were quickly overwhelmed by the weather.

The yachts caught at the storm’s center were the hardest hit. Many of these boats quickly capsized or were knocked over by the intense waves. Some yachts were dismasted entirely by the brutal winds. Sailors with decades of experience were thrown from their yachts and struggled to survive in the violent sea conditions.

Unfortunately, these extreme conditions made any kind of rescue operation incredibly difficult. If the yachts couldn’t survive the fierce winds and giant waves, what hopes did small rescue boats have?

Many of the yachts were already far from shore when the storm hit, meaning the rescue boats had to battle through the storm themselves to reach the stranded sailors. The rescue crews were at high risk and had to work tirelessly just to keep their own boats from capsizing. The last thing rescue efforts needed was the rescuers themselves needing rescue.

The limited communications technology of the time proved to be an added hurdle. Radio transmissions were often disrupted by the storm, making it difficult to coordinate rescue efforts and find all the boats that needed help.

Despite these challenges, rescue crews from the Royal Navy and other organizations worked tirelessly to save as many souls as possible. Royal Navy ships, RAF Nimrod jets, helicopters, lifeboats, and a Dutch warship, HNLMS Overijssel, all came to the rescue. While 15 sailors died, 125 were rescued by these combined efforts.

What Else Went Wrong?

Several factors beyond the sheer ferocity of the storm helped add to the tragic loss of life that day. A major factor was the lack of safety equipment and training at the time.

- Military Marine Mammals: A History of Exploding Dolphins

- A Real-Life Moby Dick? The Wreck of the Essex

Many of the boats weren’t carrying safety equipment that would be considered standard today. It was found that many of the yachts weren’t carrying life rafts, EPIRBs (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons), or storm sails. Making this even worse, many of the sailors hadn’t been trained in the use of the safety equipment they did have, or how to handle extreme conditions.

This lack of safety equipment would have been disastrous on its own. But when added to the fact many of the boats were far out to sea, it was a recipe for disaster. Rescue crews had to battle through the storm to reach the boats.

The fact many of the boats were not equipped with radios or other communication devices meant the rescue crews had an almost impossible task finding the crews. Imagine looking for a needle in a haystack that is being blown through an industrial fan.

Ultimately, the 1979 Fastnet Race led to a major rethinking of racing, risks, and prevention. It highlighted the need for better safety measures and the importance of accurate weather forecasting in offshore sailing.

The tragedy led to significant changes in the sport, including the development of better communications and navigation technologies, improved safety equipment, and more rigorous regulations. Thankfully these have all helped prevent a repeat of the disaster.

In the end, the legacy of the 1979 Fastnet Race disaster is a testament to the resilience and determination of the sailing community. While the tragedy was a devastating event, it also sparked a renewed commitment to safety and innovation and has helped to make offshore sailing a safer and more exciting sport for sailors around the world.

And through the tragedy much was learned about these new designs of boats. The hulls that made it through the storm safely, and the designs that came from them, are often still in service today.

Top Image: The 1979 Fastnet Race saw competitors trapped by a fierce Atlantic storm, and many sailors died out of the reach of rescuers. Source: artgubkin / Adobe Stock.

By Robbie Mitchell

Compton. N. 2022. 1979 Fastnet Race: The race that changed everything . Yachting Monthly. Available here: https://www.yachtingmonthly.com/cruising-life/1979-fastnet-race-the-race-the-changed-everything-86741

Mayers. A. 2007. Beyond Endurance: 300 Boats, 600 Miles, and One Deadly Storm . McClelland & Stewart.

Ward. N. 2007. Left for Dead: The Untold Story of the Tragic 1979 Fastnet Race . Bloomsbury Publishing.

Editor. 2023. 1979: Freak storm hits yacht race . BBC. Available here: http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/august/14/newsid_3886000/3886877.stm

Robbie Mitchell

I’m a graduate of History and Literature from The University of Manchester in England and a total history geek. Since a young age, I’ve been obsessed with history. The weirder the better. I spend my days working as a freelance writer researching the weird and wonderful. I firmly believe that history should be both fun and accessible. Read More

Related Posts

Joshua norton i: emperor of the americas, the shaman: spirit guide to the infinite, the indestructibles and the ancient egyptian journey to..., fogbank: lost material of the nuclear age, secrets and lies: the strange case of jeremy..., legislative hubris: how did indiana get pi wrong.

- Story Highlights

- Next Article in World Sport »

LONDON, England (CNN) -- It is still remembered as one of the worst days in the history of modern sailing.

The Fastnet race still remains one of the biggest events in the yachting calendar.

Yet the Fastnet tragedy of 1979 in which 15 people were killed and ex-British leader Edward Heath went missing helped to usher in a new era of improved safety in the sport.

It was 30 years ago today that a freak storm struck over 300 vessels competing in the 600-mile yacht race between England and Ireland.

Mountainous seas and vicious high winds sunk or put out of action 25 boats.

The British rescue attempt turned into an international effort with a Dutch warship and trawlers from France also joining the search.

In spite of the biggest rescue operation launched by the UK authorities since the Second World War a total of 15 people died. Some of them drowned and others succumbed to hypothermia. Six of those lost went missing after their safety harnesses broke.

"It was a catastrophic event that had far-reaching consequences for the sport, the biggest of which was in the design and safety of the boats," Rodger Witt, editor of the UK-based magazine Sailing Today told CNN.

"Most people in the sailing community at the time knew someone who was involved in one way or another. I had a friend who lost his father. It was devastating."

In total 69 yachts did not finish the race. The former British prime minister, Edward Heath disappeared at the height of the storm, though he later returned to shore safe from harm. The corrected-time winner of the race was the yacht "Tenacious", owned and skippered by Ted Turner, the founder of CNN.

Witt said that in the aftermath of the disaster the rules governing racing were tightened to ensure boats carried more ballast. Improvements were also made to the safety harnesses that tied crewmen to their boats, many of which proved ineffective in the tragedy. It also became mandatory for all yachts to be fitted with radio communication equipment and all competitors were expected to hold sailing qualifications to take part.

At the time of the tragedy the Fastnet race was the last in a series of five races which made up the Admiral's Cup competition, the world championship of yacht racing.

- Yachting: No sport for the faint-hearted

- 'Sail-plane' to attempt world speed record

- Norman Foster's superyacht

Competitors from around the globe attempted the route which sets off from the Isle of Wight, off the English south coast, and rounds the Fastnet rock on the southeast coast of Ireland.

Roger Ware was in charge of handling press for the event on behalf of the organizers, the Royal Ocean Racing Club. Ware said that even today the tragedy "still spooks me." The racers set off on a Saturday but it wasn't till three days later that the authorities in the English coastal town of Plymouth realized there was a problem.

The press team was based at the Duke of Cornwall hotel in Plymouth and early Tuesday morning Ware got a call from his superiors to go to the hotel immediately in order to field calls from journalists.

"The night before we'd noticed high winds but there'd been no forecast of bad weather so we didn't think much of it," Ware told CNN. "As the morning progressed though, we heard that more and more boats were missing. It became obvious a tragedy was unfolding."

Ware said the worst part for him was fielding calls from concerned relatives. "The Royal Ocean Racing Club headquarters was overloaded so calls were getting transferred to the press team.

Share this on:

Sound off: your opinions and comments, post a comment, from the blogs: controversy, commentary, and debate, sit tight, we're getting to the good stuff.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Lessons of Fastnet Race: Preparation, Respect

By Roger Vaughan

- Sept. 2, 1979

THERE are many ways to kill yourself in the name of sport. Motor racing, mountain climbing and sky diving have traditionally been the highrisk sports, with hang gliding a dangerous newcomer.

But now, with 18 contestants having perished in the recent Fastnet race, ocean yacht‐racing must certainly be considered dangerous. It was dangerous last January when two participants lost their lives during the Southern Ocean Racing Conference circuit.

Ocean racing is high risk more in theory than in fact. While the sea continues to claim lives each year, ocean‐racing fatalities have remained small. It may have cost fewer than 20 lives in the previous 50 years. Those of us who enjoy racing boats on the ocean have minimal apprehension about returning in good health. I have never met an ocean sailor who gave more than passing consideration to death by sailing.

This is not to say that one goes to sea casually. After the knowledge afforded by Melville, Conrad, Winslow Homer and others, there can be no forgiveness for arrogance. It would not do to make light of a force like the sea, or take its unpredictable moods lightly. Sailors with any sense yield before the sea. They tread softly upon its shores as a show of respect and humility that they hope, in their childlike way, will solicit protection when they are at its mercy.

Preparation must follow respect. Skills and experience must be matched with proper gear and a stout vessel worthy of the elements.

A Scare at 18

When I was 18 years old, I encountered my first big scare at sea, the 30foot waves and the 65‐to‐70‐knot winds of a hurricane during a Bermuda race. In my youthful enthusiasm, I had shipped aboard a leaky, wooden 40footer that should not have been taken 20 miles offshore. The owner, a newcomer to the sport who was finally dissauded from stuffing the bilges with live lobsters, had selected a crew of unseamanlike friends and a rusty navigator whose major accomplishment was keeping us in the storm many hours longer than any other boat in the race. The three of us aboard who could sail kept the boat going.

In the middle of that dirty gray night, when I was at the wheel running before the wind at 9 knots under bare masts, watching the huge seas trying to come aboard (some did), I suspected that maybe this was it. All of us were soaked, bruised and exhausted. But between vomiting attacks, the landlubbers kept bailing. When the dust had cleared, our navigator found Bermuda and pointed us toward it again.

Aboard Kialoa in Fastnet

Even after that episode, I never gave a thought to quitting the sport. Until my experience aboard Kialoa in the Fastnet race, I would not have been able to say why. But on Kialoa, the race was as dramatic and spectacular as it was arduous. Between crises on deck, I observed the great storm from a ringside seat.

Kialoa, a 79‐foot sloop, was designed by Dave Pedrick, formerly of Sparkman & Stephens, and built of aluminum by Palmer Johnson. Jim Kilroy, a Californian, owns her.

Kialoa is a magnificant vessel, a world ocean‐racing boat with 200,000 miles under her keel in her four years. Her mast rises 100 feet above the deck. Her large foresails weigh 150 pounds. Her hydraulic backstay is often set at a tension of 14,000 pounds per square inch. She is not only seaworthy and strong, but also fast. She has won most of the important ocean races.

On Kialoa we began to feel the approaching storm at 8 P.M. Monday evening, Aug. 13. By 10 o'clock, sleep was out of the question for those of us off watch because of the steep roll to either side and the shuddering blows that were heard and felt throughout the boat as the bow smashed unto seas. The barometer was down and dropping.

Work to Be Done

The anamometer was recording 60 in the gusts, and the seas were up. One moved about the deck in a crouch, hanging on with care while moving the clip of the safety harness from one point to another. There was work to be done. A change to the No. 5 jib (the smallest) had been called for. We raised a small staysail to keep the boat in balance between jibs and took the No. 4 down with difficulty. An hour later we would have had to cut it loose.

As it was, the spray coming off the bow struck us like whips, and only our safety lines clipped to the weather side kept us from sliding into the sea. Raising the No. 5 was out of the question. The wind was increasing. We would sail with the small staysail and the main reefed to maximum.

With the storm full on us, we took positions on the high side of the deck and held on. The three best helmsmen took turns facing painfully into blowing scud that stung like sand, looking for the optimum path through seas that lifted us up and up and rolled under us or struck us broadside, full force.

Driving was exhausting. The helms man would yell a warning the moment he knew he had been beaten by one of the monsters. We would double our grip and tuck our heads in as hundreds of gallons of solid water tried to batter us off the deck. Recoiling from one such wave, two crewmen fell against the yacht's owner, Jim Kilroy, crushing him against a winch. He went below in pain for the remainder of the race with two broken ribs.

Unlike the claustrophobic, ominous feel of most storms, this night presented the striking contrast of clear skies alight with a full compliment of stars. Occasional clusters of low, fastmoving fleecy clouds would pass through. The moon was high, threequarters full and brilliant, illuminating the steep seas with cold, eerie light. When clouds masked it, its beams peeked through to turn small patches of ocean to pure pounded silver. Astern, the big dipper was full to brimming.

Kialoa was reaching at 10 knots under minimal sail. Her fine racing bow sliced into the seas, carving off hunks of ocean that were splattered to either side as foam and heaved high into the air and blown into the sails. The water was thick with globs of phosphorescence that would stick on the mainsail and glow for a moment, or speed off to leeward on the wind like sparks from spent fireworks. From her mad dash through the storm, Kialoa left a swath of pure white foam astern fully 200 yards long that shimmered like a snowfield in the moonlight. I yearned to see us from a nearby vantage point. We must have been a sight.

The Run Toward Land's End

Before dawn, we rounded the Scilly Isles and ran toward Land's End on the southwest corner of England. With the seas and wind astern, the boat stabilized. Our speed increased.

With morning light, we got our first good look at the storm we had contested for seven hours. The ocean was in a frenzy. The sun rose in a clear sky, spotlighting the cresting caps of huge breaking seas on all sides. Streaks of wind raced down the fronts of waves into the troughs and up the backs of the next like schools of fish in full panic. Kialoa chased after them, pursued in turn by 30‐foot walls of deep blue water that hung above the stern.

Kialoa began surfing like a dingy. Sheets of glistening water flew from her bow as if it were a water ski in a tight turn. Her speed never dropped below 15 knots. Planing on one set of waves that must have measured 40 feet, the speed gauge more than once registered an incredible 21 knots.

With her bow hanging out of the wave as she took the drop, Kialoa felt as light as a feather and in full control. We sat on deck in stoned silence, marveling at her performance. In tense concentration, the helmsman would spin the big chrome wheel with quick hands, settling her in the groove as her stern rose on the wave, then break into a wide smile as she took off on her own, the speed gauge easing toward 20. Spontaneous cheers erupted from us. For nine hours, until we crossed the finish line at Plymouth, we sailed like that.

During the race we had listened to radio reports, the calls of distress and the heroic efforts of the air‐sea rescue service. The grim statistics to come would cast a pall upon the event. But after 30 years of sailing on the ocean, it remains that the 1979 Fastnet race was the greatest sail of my life. The sights and sounds of that strangely clear stormy night — of wind and sea run amok — were a spectacle the likes of which I shall probably never again see.

People go to sea for many reasons. For some there is a magnetic pull of astrological origin. Others treasure the feeling of openness that is exceeded only in space, or the unusual community of people on a tight ship. The performance of a well‐designed vessel is also one of the great joys.

Cosmic Unity

Beauty of the sort that amounts to religious experience must rank high on my personal list. I am not a churchgoer. But always, at sea, my agnosticism falters. For at sea is when the concept of cosmic unity is most difficult to deny. Of all the ocean moods that reveal this, a storm the magnitude of Fastnet 1979 has the most sobering impact.

Circumstance, not choice, places one in the middle of such a mallstrom. While the encounter is not one a sane person openly wishes for, going to sea implies taking the risk. Therefore, when it happens, there can be no recriminations, no regrets. One must respond the best he can to the test and only enjoy the rare opportunity — the privilege, in fact — that brings vessel, gear and men close to an outer limit of strength, resourcefulness and endurance.

We did not beat the storm on Kialoa. But it did not beat us, either. And that is the best one can do.

Few sailors who race the oceans give more than a passing thought to death. But few go to sea without careful preparation, and all tread ocean shores with respect. In Fastnet race, Grimalkin was dismasted. Here a British Navy helicopter crewman boards stricken vessel seeking survivors.

Associated Press

Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

1979 Fastnet Race: the kindness of strangers

- Sophie Dingwall

- June 7, 2022

Brett Dingwall shares how the selflessness of others made all the difference after the harrowing events of the 1979 Fastnet Race

Brett Dingwall raced in the Contention 33, Lipstick during the 1979 Fastnet. The yacht was knocked down multiple times. Credit: Sophie Dingwall Credit: Sophie Dingwall

Anyone in the sailing fraternity recognises the Fastnet Race as one of the world’s most notoriously tough endeavours, even for the most skilled sailor.

The 695-mile route starting from the English south coast, around the Fastnet rock, a rather bleak isolated protruding teardrop situated in the Celtic Sea, and back again has been well documented.

A spot onboard this sought-after race is on many bucket lists and attracts people from around the globe.

But there’s one race edition in particular that stands out, one that has warranted book publications, and even resulted in changes to safety measures for vessels that stand today.

The year unforgettably etched into the memory of both those involved and succeeding competitors is the infamous 1979 Fastnet Race .

The rescue of the 1979 Fastnet crews was one of the biggest operations during peacetime in the UK. Credit: Getty

Meteorologists and journalists reported on the natural phenomenon that formed over the Atlantic Ocean and swept across the racecourse, leaving behind harrowing destruction and chaos.

Vessels, like scattered debris in the vast expanse of the open water, were left battered and bruised, and limped onwards in search of shelter.

In time, the victims of this perilous storm shared their stories and people everywhere were rocked by the tragic loss of life.

The glimmer of light, piercing through the thick blanket of cloud as the storm subsided, was a reminder to us all that when such a catastrophe occurs, acts of kindness will always prevail.

In our minds the 1979 Fastnet paints a scene of despair, loss, sadness and fear – all of which are credible descriptions of one of the biggest disasters in ocean racing history.

But I am going to fill in some gaps, touching on the small acts of kindness and the bits that are so easily missed that do, in fact, restore faith in humanity.

We have been using various forms of boat to travel for longer than we’ve had a written language.

Around 4,000 people, including personnel with the Irish Naval Services, lifeboat volunteers and crew from commercial boats assisted in the rescue operation. Credit: Sophie Dingwall

The idea of pushing off from the safety of the shore to the uncertainty that lay ahead would seem mad to most, but not the sailor.

The sailor is drawn to uncertainty and develops a feeling of freedom because of this.

The formidable characteristics of watermen and women alike was the driving force in the 1979 Fastnet rescue mission, a huge undertaking for all involved.

There’s a saying ‘a sailor if nothing else is resourceful.’ However, the best ones are optimistic too.

We look back on one man’s memories and personal experiences of this race.

He reminds us that even the smallest acts of kindness can have profound effects on those around us.

Then, as now, the hints of Gelcoat and epoxy that covered his clothes, untidy exterior and rough hewn but steady working hands left no doubt as to the occupation of this man; he was of course a boat builder.

Brett Dingwall constructs Hornets, Toys and Merlin Rockets in his Mill Hill workshop in North London, which he admits is not a typical location for a boat builder to set up shop.

But his work was skilled, his character enchanting and, combined with his renowned reputation, he made it work.

Accidental 1979 Fastnet crew

In his typical laid-back approach to life, Brett accidentally found himself hitching a ride with his client, who happened to also be his accountant, on board the 33ft Contention, Lipstick .

Brett’s true passion was dinghy racing; he revelled in the fast-paced aggression that surfaced on the racecourse and the tactical decision making that exercised his mind.

The fact was he felt indifferent pursuing what he considered to be a long slog offshore.

‘It was another life experience, so I thought why not? It would be a shame to turn it down but yacht racing wasn’t my thing.’

Brett Dingwall prefers dinghy racing to offshore racing, liking the tactical decisions he has to make while sailing the course. Credit: Brett Dingwall

Crew nowadays train for hours on the water to build a strong team, but Brett had never stepped foot on the boat before, let alone met all the crew.

Their setup was no slick operation either; these men were hashed together and, like so many others, were unaware of the fury that was set to come.

‘We weren’t geared up like most boats are today,’ says Brett. ‘We had a radio and charts but it was pretty basic. I don’t think such a catastrophe would happen today with all the technology we have at our disposal.’

Having crossed the start line, ‘The weather wasn’t all that bad and we were going like the clappers,’ explains Brett.

But as they edged out of the English Channel the heavens blackened above them and merciless weather quickly developed.

The crew abandoned any competitive thoughts and engaged survival mode for the vessel.

Brett’s attitude towards the situation remained positive though.

Despite the terrifying conditions he encountered that day, Brett recalls feeling in awe at the spectacular power of nature. Credit: Sophie Dingwall

‘I soon realised the severity of the storm and I couldn’t believe the height of the waves. I remember thinking, “Wow! Isn’t nature spectacular!” I wish I had had a camera to take a photograph.’

As the yacht became uncontrollable, the crew dropped the sails and lashed them to the deck.

A confused sea state added to Brett’s labour on the helm and far too often, waves swept over the deck, engulfing the whole yacht.

As fear transmitted through the crew, a consensus to enter the liferaft emerged.

‘I didn’t want to get into the liferaft , not while the boat was still afloat; it didn’t make any sense. I’m almost certain we lost it at some point.’

Instead, measures were taken to limit damage.

An inquiry was held following the 1979 Fastnet, which tightened up racing rules including the introduction of Safety & Stability Screening for boats. Credit: Kurt Arrigo

Lines, buckets and almost anything acting as a drogue were thrown off the stern in an attempt to slow and steady the vessel.

‘It was quite impressive. The speed instrument often went off the scale down the waves and there was a point when I knew for certain that the boat would capsize.’

Brett secured himself to the cockpit with his harness and wound a rope around his hand a few times: ‘I didn’t want to rely solely on my harness line, so I tried to take some of the load off when I hit the water.’

His bare-knuckled grip around the tiller guided Lipstick through the mountainous waves that seemed to have no rhythm or mercy.

The ricochet of the trembling bones was felt throughout the yacht and with each blow, a deafening suspense and finally relief as she held together.

But the inevitable was coming.

Destructive waves

‘I was helming for the first capsize and we fully inverted. As we went over, it was as though the boat continued making way through the water, it didn’t seem to stop! It’s quite amazing what the boat managed to withstand.’

Insignificant in size, Lipstick remarkably righted herself against the power of the sea.

The main hatch had been damaged during the capsize, leaving a large hole in the companionway.

With no drill to be found, Brett began to create holes with a screwdriver and hammer, to secure the hatch in place with a few rogue screws to avoid it being torn off entirely.

In true English manner, one of the crew piped up, ‘Don’t you think you’d better ask the owner first before making holes in his boat?! He might not be very happy about that.’

Aware of the gallons of water flooding over the deck and risk of yet another capsize, Brett won’t recall his exact response, but we can guess the language is not suitable for publication.

The Contessa 32 Assent was one of the survivors of the 1979 Fastnet, and took part in the race again in 2019 following restoration. Credit: Nic Compton

Maydays seemed to run continuously over the radio and flares lit the sullen sky. ‘We could see and hear other boats in distress, but we were too small to help anyone around us as we had almost no steerage by this point.’

Lipstick suffered multiple knockdowns and the interior and its contents were quite literally turned upside down.

‘It was really strange being stood on the ceiling of the boat and it seemed to take forever to come upright. But the whole experience was exhilarating.’

It’s got to be in the blood, as Brett’s cousin Ross happened to be competing in the race as a navigator onboard Rrose Selavy , a Contessa 43.

Previously named Moonshine , she was a British Admiral’s Cup boat but was sailing under the Italian flag.

He describes similar conditions, but the yacht sustained barely any damage and there was no walking on the ceiling.

However, mutiny broke out as half the Italian crew wouldn’t step foot on deck, leaving but a few bodies to battle against the elements.

Brett Dingwall is a boat builder, specialising in Hornets, Toys and Merlin Rockets. Credit: Sophie Dingwall

However, Ross and the crew made it around the rock, which was no small achievement.

The change in depth when rounding the rock created monstrous waves and the crew only escaped a knockdown by the skin of their teeth.

The weather soon subsided and when checking for water in the bilge, Ross found an undamaged crate of white wine.

‘A real miracle. It felt like a water to wine moment!’ he said. How could they ignore such a sign? ‘I pushed the cork in and we drank the first bottle. By the time we got to Plymouth, we were completely pissed. When we got off the boat people were looking at us thinking, oh the poor devils, they’ve faced such terrible conditions they can’t even walk straight!’

Although Brett and Ross shared similarities in conditions, their experiences onboard were rather different.

Interestingly, their outlook as a whole remains uncannily similar.

As Ross said: ‘In a horrid sort of way, it was quite exciting.’

When the worst of the weather had passed for Brett, the slight ease in conditions gave him some time to breathe, but as the adrenaline began to wear off, the effects of the passing hours set in.

Darkness overthrew the daylight hours and because of the extreme weather and poor visibility, the logbook lay bare.

Maintaining a fix was near impossible and the limited technology and lack of navigation systems meant that Brett and the crew now had no idea where they were.

Selfless acts of others

Typically, fishing boats get a bit of a bad name; their casual approach to the rules of the road often go amiss amongst the yachtie folk, but the French trawler, Cap der Guy was a rare welcoming sight.

The rough waters meant a risky transition on board, but every effort was made to get off the boat.

The French fishermen offered nutritional essentials, Gauloises cigarettes and real coffee.

‘In those days everyone smoked like crazy, but I can’t remember being able to light up a cigarette until then!’

Brett Dingwall recalls the pain he felt in his hands from gripping rope which was his lifeline beneath the capsized yacht. Credit: Sophie Dingwall

Somewhat refuelled and now bound for Ireland , Brett slept propped up amongst pots and nets as the French transported the crew and vessel to solid ground.

Lipstick was taken into Dunmore East Harbour in southern Ireland, where some boats had already made it back.

Hundreds selflessly risked their own lives to help those in need; these heroic rescue efforts by many crew on ships, trawlers, lifeboats and aircraft proved invaluable.

Looking back on such an event requires reflection as well as remembrance.

Quite often this is where the stories end but the truth is, the rescue continued. The days of incessant turbulence under Brett’s feet left him unsteady.

He tacked his way up the pontoon, bouncing off piles as he went but unfortunately for Brett this wasn’t due to wine, for he was not blessed like his cousin.

Continues below…

1979 Fastnet Race: The race that changed everything

Nic Compton investigates how the UK’s worst sailing disaster - the 1979 Fastnet Race - changed the way yachts are…

Why a yacht makes the best liferaft

A liferaft is reassuring, but only to be used as an absolute last resort. James Stevens explores the main scenarios…

Heavy weather sailing: preparing for extreme conditions

Alastair Buchan and other expert ocean cruisers explain how best to prepare when you’ve been ‘caught out’ and end up…

Tracy Edwards: who is the sailing trailblazer?

Sophie Dingwall talks to Tracy Edwards about her sailing life, her campaign for girls’ education and what is next for…

His hands were left sore and bruised.

Mere strands of polyester fibres wound together to form a ‘bit of rope’ had become a significant lifeline in his survival while beneath the capsized yacht.

Longing to speak to his family, Brett continued the uphill struggle in search of a phone.

The sailing club had opened the clubhouse especially to accommodate the crews and a bucket of change could be found next to the payphone, while hot meals were consumed in the comfort of the club at no expense.

‘I phoned my wife – we had twin boys that were two at the time. My wife was worried as it had been relayed that only five were brought back on board the trawler and we were a crew of six, but luckily this was lost in translation. We all made it back safe.’

A warm Irish welcome

Lipstick was in disarray, but they were back safe and any work to be done could wait a while.

Local families took the weather-beaten sailors into their homes, no questions asked, and no timescale given; the Irish welcomed them as if they were their own.

Blessed with charm and charisma, their soft accents and friendly hospitality is renowned all over the world.

Those lucky enough to have landed here can certainly vouch for that.

Blurry with exhaustion, Brett accepted the gracious offer to retreat to a local family’s home; not that they’d have taken no for an answer, where he slept and slept and slept some more.

The residents of Dunmore East opened their homes to the 1979 Fastnet survivors. Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

‘While on the boat I was of use, I had something to contribute but I remember thinking I must pace myself to be able to keep going. I was drained but there was one chap on board who kept morale high, and I think his role was most important. Once I’d made it ashore, I relaxed somewhat and allowed myself to be looked after.’

Unsure of the number of hours that had passed, Brett finally woke to find the family had rooted through the chaos on board Lipstick , gathered his belongings and set them out on the side.

His sodden, salty clothes had been washed and hung out to dry, they had taken care of everything.

The heavenly smell of brewed coffee and bacon wafted throughout the house, the smell alone woke Brett from his deep slumber, and he eagerly made his way downstairs to find a hearty Irish breakfast on the kitchen table.

‘For me, it wasn’t frightening at the time, I didn’t have a chance to think too much. I knew I had to keep going and keep the boat together, but I was quite numbed afterwards. I could not focus on the people that took me in for I was so exhausted. It was days before I even knew anyone had lost their lives in the race and I thought to myself how lucky I was.’

The hospitality Brett was met with in Dunmore East was warm and genuine.

These memories of support from strangers are still present today and largely override any dire flashbacks.

You won’t find Brett sat in the pub relaying tales of woe; instead he highlights his gratitude to the Irish, who opened their homes and hearts during one of sailing’s bleakest moments.

Brett says: ‘The experience was exhilarating, it roused all the senses, and this was quite positive for me as it helped put things in perspective. It was clearer than ever before what I valued in my life.’

Relieved to have reached Dunmore East, Brett couldn’t get home quick enough.

Brett Dingwall prefers to recall the warmth and kindness he received from strangers rather than talk about the harrowing events of the 1979 Fastnet Race. Credit: Sophie Dingwall

He was running his own business, had a young family to support and days off were few and far between, but arriving home, he knew that time with his family was most important.

‘I took my wife and the boys to Whipsnade Zoo the day I arrived. Even though the boys were so young, they had already spent plenty of time on the water but we decided a day on solid ground was best!’

The most challenging times are often when people learn the most about themselves.

The trickiest parts of life give a balanced perspective and shine a light on the positives which can otherwise remain unnoticed.

Take from this story, the mindset of an optimistic sailor whose attitude has bettered him in everyday life and future challenges.

‘I was in hospital for quite a long time and I automatically reverted back into the same mindset as when I was sailing. I reduced my aspirations, took everything as it came and felt grateful for what I had and for the small things that improved my day.’

The 1979 Fastnet Race

The 1979 Fastnet was one of the world’s worst sailing disasters and triggered the largest ever rescue operation in peacetime.

A worse-than-expected storm on the third day brought Force 10 winds which ravaged the 303-strong fleet, leaving 24 boats abandoned, five boats sunk, 136 sailors rescued and 15 dead.

The rescue operation involved around 4,000 people, including personnel with the Irish Naval Services, helicopter crews, lifeboat volunteers and crew from commercial boats.

The subsequent inquiry resulted in improved safety equipment and highlighted several weaknesses in yacht construction such as cockpit drainage, the arrangement of stowage, and changes in the construction and design of the main companionways in order to improve watertight integrity.

Enjoyed reading 1979 Fastnet Race: the kindness of strangers?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price .

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals .

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram.

Published on December 9th, 2013 | by Editor

Reflections on the 1979 Fastnet Race

Published on December 9th, 2013 by Editor -->

Ned Shuman, Captain, USN (Ret), 82, passed on December 4, 2013. During his eventful life , he was Officer-in-Charge and senior coach of a crew of midshipmen during the tragic 1979 Fastnet Race which incurred 15 fatalities. Here is the report Ned submitted in April 1999 … On 11 August 1979, the U. S. Naval Academy yacht Alliance crossed the starting line off the Royal Yacht Squadron in Cowes, Isle of Wight, England, on the biannual Fastnet Race. Alliance was a 56-foot aluminum sloop. On board were Lieutenant Commander Chip Barber, civilian coach Bob Smyth, Ensign Kevin Mathison, eight midshipmen, and yours truly – the officer-in-charge.

The forecast predicted light winds. On the morning of the start, the crew thought to lighten the boat by unloading several of the heavy-weather sails. My orders to put them back aboard were met with a general lack of enthusiasm. I pointed out to the skeptics that the 605-nautical-mile Fastnet Race had a nasty reputation for rough conditions in spite of forecast weather.

The boat was strong and the crew had just won the TransAtlantic race from Marblehead, Massachusetts, to Crosshaven, Ireland, beating such well known ocean racers as Kialoa , Ondine, Condor, and Sleuth – an extraordinary achievement. They had done well in the Cowes week events including the 217-mile Channel race; they were tough, experienced, and ready. All Category One equipment was on board.

During the night of 12/13 August, Chip, our navigator, began to get reports of possible heavy weather. Nothing we couldn’t handle; we had experienced 40+ knot winds on the TransAtlantic. It didn’t take long to go from a number one jib and full main (big sails) to bare poles as the seas and wind built; shortening down, we destroyed the number three jib and had to cut it loose and throw it over the side. We were 60 miles from Fastnet Rock and getting pasted.

Finally, we were able to hoist a storm jib and storm trysail (the smallest sails). There is nothing like the sound of waves breaking over an aluminum boat to get one’s attention – and it was dark, real dark. Most of the crew was sick, but the boat was under control and holding up well. The shore was to leeward, so there was no place to run.

We became aware of a massive search-and-rescue attempt under way by both ships and helicopters, which did nothing to alleviate the already high pucker factor. Chip nailed Fastnet Rock using dead reckoning, a radio direction finder, and a fathometer. No easy job in the days before GPS; Loran C was not available, and the weather precluded celestial. As the wind eased and the seas settled, we were able to bend on more sail. We signaled a Royal Navy helicopter that we were all right and would complete the race.

When we docked at the Royal Marine Base in Plymouth, we heard the bad news: 15 fatalities, 5 boats sunk, and 24 boats abandoned. Of the 303 starters, only 85 finished. All of the fatalities occurred on boats less than 39 feet long and only one boat over 39 feet was abandoned. On the positive side, one ensign and eight midshipmen – Hampshire, Fish, Aruffo, Cheney, Donofrio, Kineke, Mortonson, and Perry – had passed a stiff test with flying colors.

I have often compared ocean racing in bad weather with being a prisoner of war, an environment with which, unfortunately, I have some experience. Harsh conditions, cramped quarters, bad food (really bad on boats stocked by midshipmen), and diverse personalities. Instead of the guards beating on you, mother nature takes over. You can’t get out so you make the best of it. It’s a character-builder.

Here we are, 20 years later, with a similar occurrence on the Sidney-Hobart race. What have we learned? First, from what I have read I think the conditions on the Sidney-Hobart were worse. Second, as a result of the 1979 Fastnet race offshore safety has made massive improvements. Equipment is superior, race management is better, crews are better prepared, and arguably, boats may be better.

What happened? Simply stated, the ocean is capable of providing more pain than man or machine can endure. All race committees require the participants to sign disclaimers that state that the skipper is responsible for his boat and that the decision to race or not to race is his alone. Does that mean that the race committee is blameless if they knowingly start a race in advance of an impending storm? I don’t think so. I am not concluding that the Sidney/Hobart race committee was negligent or responsible for the disaster. It is still being investigated. Ocean racers, aviators, skydivers, balloonists, mountain climbers, downhill ski racers, etc., are risk takers. No risk, no fun. They don’t back down or quit easily. I have long maintained that if someone sponsored a race from Newport to Bermuda in J-24s it would probably be oversubscribed.

Who can protect these risk takers from themselves? Maybe no one. Race committees have postponed major offshore races based on weather, but it is always a tough call.

The difficult question remains: How much risk and expense should the various rescue units of the world accept in rescuing the participants of these ill fated endeavors? Perhaps the panel at this month’s Naval Institute Annual Meeting can address the issue.

Captain Shuman , a naval aviator, was shot down over North Vietnam in March 1968 and spent five years as a prisoner of war. He wrote “Back to Hanoi,” published in Proceedings , October 1992, pp. 81-85.

Tags: 1979 Fastnet Race , Edwin Arthur Shuman III , Fastnet Race

Related Posts

Keep packing passport for Fastnet Race →

What we do for fun →

VIDEO: Stories from the Fastnet Race →

Overall winner set for 2023 Fastnet Race →

© 2024 Scuttlebutt Sailing News. Inbox Communications, Inc. All Rights Reserved. made by VSSL Agency .

- Privacy Statement

- Advertise With Us

Get Your Sailing News Fix!

Your download by email.

- Your Name...

- Your Email... *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

The Fastnet Yacht Race 1979

The story of the Force 10 gale which decimated the 1979 Fastnet race, the last of the Admiral’s Cup events in that year. A massive search and rescue operation was begun as half of the 300 yachts competing went missing in a 20,000 area square of the Irish Sea. The death toll was 15, and the ramifications are still felt today with the increased safety requirements introduced in the aftermath

BBC Director: Nat Sharman Series-producer: Greg Lanning Scriptwriter, Writer: Christabelle Dilks

No related posts.

Leave a Comment Cancel

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Email Address:

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Fastnet 79: Could sailing’s biggest disaster ever happen again?

- Elaine Bunting

- November 7, 2019

This year marked the 40th anniversary of a race never to be forgotten. Elaine Bunting looks back at crews’ experiences of the 1979 Fastnet Race

Helicopter winchman goes to Grimalkin. Photo: PA Archive

Back in 1979, Ted Turner’s Tenacious won the Fastnet Race , with a corrected time of 3 days 8 hours. Over the last 30 years the average speed across the 605-mile Fastnet course has increased phenomenally: at the elite end, the fastest Ultime trimarans complete the course in just a third of Tenacious ’s time. Yet for the smallest yachts in the race, the race can still take five full days.

Yacht design has changed enormously in 30 years, but even more so communications, navigation and access to weather information. So it begs the question of whether a tragedy on such a wide scale could ever happen again?

Navigating in 1979 was a world away from today. Since today there is never a doubt as to our position, the role of the navigator is more one of tactician and strategist. Back then, nav aids such as Loran and Decca were specifically banned and sat nav, then in its infancy, was also prohibited. The tools for the navigator were a sextant, a radio direction finder (RDF), compass and experience of dead reckoning navigational skills.

Royal Navy helicopter comes to the aid of Camargue . Eight crew were rescued at 1033 on 14 August 1979. Photo: Getty Images

Communications were poor. VHF or MF radio was not mandatory. The larger yachts mostly carried VHF but only an estimated 25% of the smaller yachts did. Radio sets were heavy, cumbersome and expensive, and also power-hungry on yachts with small capacity batteries.

Professional navigator and columnist Mike Broughton was just 17 when he took part in the 1979 Fastnet , the youngest competitor in the race, along with Yachting Worl d’s former technical editor Matthew Sheahan . Broughton was racing Hullaballoo , a 3/4 Tonner.

“It was all about the shipping forecast in those days. The news came from the radio. There was gossip that a storm was on the way and we knew the Prime Minister [Edward Heath in Morning Cloud ] had retired,” he explains.

Article continues below…

Fastnet Race 1979: Restored survivor Assent heads back to the Rock

It’s a gloomy, grey afternoon on the Solent and I’m in a camera boat taking pictures of a yacht sailing…

Fastnet Race 1979: Life and death decision – Matthew Sheahan’s story

At 0830 Tuesday 14 August 1979, aged 17, five minutes changed my life. Five minutes that, despite the stress of…

“The navigation was quite primitive. We did have RDF, but on the Irish coast it was a reciprocal and if you had a 5-10° error, with no cross-cut you never knew [exactly] where you were. We didn’t even have VHF. We had a French search tug signalling Kilo, ‘I wish to communicate with you’, in Morse code.”

Now yachts not only have EPIRBs, but AIS, often radar, and access to weather through multiple means, not least long periods of 4G mobile phone coverage. Crews carry PLBs and AIS personal locators. YB trackers allow teams to see each other’s positions, tracks and speeds.

Safety gear is checked and of a regulated standard; 40 years ago, only a very few tether lines met any agreed standard, and liferafts without drogues were apt to blow rapidly downwind, or even (as happened) to disintegrate.

A yacht 150 miles north-west of St Ives under jury rig. Photo: PA Archive

Clothing was poor by modern standards, and leaked as a matter of course. Hypothermia was a real risk. Attitudes to safety gear were also very different; lifejackets and harnesses were not routinely worn. Crews were much less drilled and there were no mandatory qualifications.

While one could argue that, as a society, we may be more risk averse than we were 40 years ago, we are also better informed. Access to better forecasts allows skippers to decide earlier whether or not to press on. The number of retirements seen in any Fastnet Race is to its credit, and not a negative. If a storm of similar ferocity were to affect the race again, it is almost certain many would seek shelter rather than press on.

But could a storm ever cause another Fastnet disaster? Very possibly. The sea state that brewed so violently 30 years ago would probably still see boats rolled and damaged. Even short-term forecasts can be sufficiently inaccurate to lead to unforeseen conditions, duration of peak winds or sea state, just as we saw during the race this year in August.

A well equipped 1979 yacht, with Sailor VHF radio and RDF

“Boats are better now, organised better, the weather forecasts better,” says Mike Broughton. “But as yachtsmen we are easily belittled by 40-45 knots of wind. And boats get more radical. When you hear of inshore yachts doing it that are thin and lightly built, and so wet that guys didn’t go below, you wonder if it is the same trend as in 1979. But the training and the gear is just so much better.”

The 1979 Fastnet storm

The first indication of a storm to come was at 1505 on Monday 13 August, when the BBC Shipping Forecast broadcast the following warning: ‘Sole, Fastnet, Shannon. South-westerly gale Force 8 imminent.’ By the next broadcast at 1905 that had been upgraded to: ‘Force 8 increasing severe gale Force 9 imminent.’

It was while hand-drawing the 2200 chart around a low pressure of 978mb that forecasters realised the isobars were tightening up to such a degree that it was inevitable a Force 10 would occur in the Fastnet sea area. But the length of the shipping forecast storm warning was not enough to allow the majority of competitors to run for shelter.

Satellite picture of the storm as it was developing on 1532UTC 13 August 1979

The strongest winds were in a corridor to the south of Ireland, which lay across the race fleet, bringing winds of 60 knots plus. The growth of the sea state was initially puzzling, as it increased ahead of the wind.

Some competitors later reported 6-7m seas and, later, huge, confused cross seas. Although estimating wave heights is very difficult from a yacht, claims of huge waves were substantiated by a report from a Nimrod pilot on 14 August of wave heights of ‘50-60ft’.

Satellite pictures showed a well-defined, active cold front, and this was followed by a trough, shown on the later charts. Most importantly, the change of wind direction behind the trough was in the region of 90°.

The strongest winds arrived as the pressure rapidly rose after the trough. Gusts contained within the leading edge of squalls could have been half as much again as the average wind speed (or perhaps more than that), making reported gusts of 80 knots realistic.

This change in the wind direction was the one overriding factor that generated problems for the boats. In other circumstances, yachts might have run under bare poles or towed warps, but on this occasion crews had no chance and yachts were knocked down repeatedly.

Storms of this intensity, or greater, are not unknown in this area, though they are rare in summer. In October 2017, a record wave height for Irish waters of 26m was recorded at the Kinsale gas platform off the Cork coast. Some of the highest waves in 1979 were also recorded by the Marathon platform in the same gas field.

First published in the October 2019 edition of Yachting World.

- Nautic Shows

- Amerisca’s Cup

- Classic Yachts

- Motor Yachts

- Sailing Yachts

- Superyachts

- Yacht Clubs

- Yacht Club de Monaco

Yacht Club Monaco’s Captains Forum – LIVE

Day 1 – valencia 52 super series royal cup, unicredit youth america’s cup – semi-finals – live, luna rossa prada pirelli team’s jimmy spithill, superyachts and the super rich – full episode 2024, k1 britannia’s story – the kings yacht, oceanslab – race to zero emissions, riva 76′ bahamas super, the perfect balance – ferretti group, rafa nadal captains a team in the e1, the formula 1 of the sea, “mayhem at lake george” annual boating event lives up to the name, candela c-8 flying above the waves, brabus shadow 900 | 300nm (550km) offshore in 9.5 hours , emirates team new zealand launched their prototype hydrogen-powered foiling chase boat in auckland today, the sailing sixties bbc documentary, j class yacht revival, 44cup calero marinas 2024 review, recap – j class world championship 2017, sailing 60 knots wind on a swan 57, basque country international jet ski cup 2024, fuerteventura kitefoil international open cup 2024, patri mclaughlin sets new kitesurfing world record 72ft at jaws, sp80 – the boat designed to break the world sailing record, marina opencall – monaco smart & sustainable marina rendezvous 2024, the sydney to hobart yacht race 1998: remembering a deadly storm, the fastnet yacht race tragedy of 1979, tracy edwards – maiden round the world skipper, baltimore: ‘mass casualty event’ as bridge collapses after being hit by ship.

- Nautic Life

The story of the Force 10 gale which decimated the 1979 Fastnet race, the last of the Admiral’s Cup events in that year. A massive search and rescue operation was begun as half of the 300 yachts competing went missing in a 20,000 area square of the Irish Sea. The death toll was 15, and the ramifications are still felt today with the increased safety requirements introduced in the aftermath.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Rescue and salvage operation in the azores.

RECOMMENDED VIDEOS

Louis vuitton cup final | press conference, editor picks, popular posts, louis vuitton preliminary regatta – barcelona | day 1 – live, emirates team new zealand’s taihoro suffers lift mishap after day 1..., sailgp christchurch bids farewell: coutts cites ‘minority groups’ as cause for..., popular category.

- Amerisca's Cup 127

- Tripulante 18 32

- Life Style 3

- Motor Yachts 3

- Nautic Magazine

- Advertising

Practical Boat Owner

- Digital edition

Lessons learned from the sinking of Morning Cloud 3

- Rupert Holmes

- September 2, 2024

50 years on, Rupert Holmes looks at what the Morning Cloud 3 tragedy taught us about heavy weather sailing

Morning Cloud 3 was designed by Sparkman & Stephens. Credit: Ajax News & Feature Service/Alamy Credit: Ajax News & Feature Service/Alamy

Half a century has passed since the loss of Ted Heath’s 45ft ocean racing yacht Morning Cloud 3 , which claimed the lives of Christopher Chadd and Nigel Cumming, two of the seven crew on board.

The yacht was severely damaged by two mammoth waves off the coast of West Sussex on 2 September 1974; the remaining crew abandoned ship before being rescued.

From the start, former UK Prime Minister Heath wanted to share as many details as possible about the tragic accident so the sailing community at large could learn from the experience.

The skipper of Morning Cloud 3 on that fateful voyage was Don Blewett, who wrote a long account, which was condensed and edited by yacht designer and journalist Julian Everitt for the Royal Ocean Racing Club’s magazine, Seahorse .

The salvaged remains of Morning Cloud 3 . Credit: Ajax News & Feature Service/Alamy

The sinking of Morning Cloud 3 made headlines around the globe given Heath had been Prime Minster until only seven months earlier, and had been leader of the Conservative Party for almost a decade.

It also raised plenty of concerns in the sailing world, as this was a state-of-the-art yacht built without regard to cost for one of the most successful teams in the sport.

Heath’s previous boats had won iconic offshore races including the Sydney Hobart Race, the Admiral’s Cup and the Round the Island Race.

It’s often asserted that older boats are stronger and more seaworthy than newer models.

However, even though there are now more boats on the water, events such as the loss of Morning Cloud 3 are rare today.

Ted Heath owned five offshore racing yachts, all called Morning Cloud. Credit: Getty

What can we learn from this incident? And what else have we learnt over the past 50 years?

It’s also important to note that the science behind big breaking waves and weather forecasting has changed significantly since 1974.

In addition, we now have a better understanding of the forces a yacht must withstand in severe conditions and far superior tools for structural engineering calculations.

Today’s epoxy resins are also far more effective than the glues available in the early 1970s.

Timeline to the Morning Cloud 3 tragedy

First, let’s look back to the events of 2 September 1974. Morning Cloud 3 , a year-old custom offshore racing yacht designed by Sparkman & Stephens and built by Clare Lallow in Cowes was being delivered from Burnham-on-Crouch on the East Coast to the Solent, a distance of around 160 miles.

This was at the end of Burnham Week, and Morning Cloud 3 wasn’t the only yacht making the same trip.

The Swan 41, Casse Tete left at a similar time but was slightly faster, reaching the relative shelter of the Solent before the strongest winds.

Just before Morning Cloud 3 ’s crew cast off from Burnham, the 1155 Shipping Forecast reported that Force 5-7 southerly winds were expected for sea areas Humber and Thames; shipping in Dover and Wight should expect Force 6-7 westerly winds, locally Gale 8.

It would therefore be a windy and uncomfortable voyage, but still well within the conditions that a well-found large yacht with an experienced and strong crew should be able to handle.

By nightfall, they’d dropped the headsail and the main was rolled down to around one-third of its full-size area, with 15 turns of the sail around the boom, since the breeze had picked up considerably.

Morning Cloud 3 was built at the famous Lallows yard on the Isle of Wight. Credit: Ajax News & Feature Service/Alamy Stock

“Although the wind was gusting Force 8 the boat was comfortable and everyone had some sleep,” Blewett reported.

The 0030 Shipping forecast on 2 September was for up to Gale 8, but by 0500 conditions had moderated to a Force 5-6 with occasional Force 7.

Nevertheless, the next forecast at 0600 on 2 September (18 hours after departure) was: southerly Force 6-8, veering south-west, perhaps Severe Gale 9 later. Rain at times. Moderate.

“I again briefly entertained the idea of putting into Dover,” wrote Blewett, “but we were sailing at 8½ knots on course, with a fair tide.”

By 0945 they were abeam of Dungeness then tacked offshore near the Royal Sovereign platform, a little to the east of Beachy Head, to gain some sea room.

The next leg to the Owers, south of Selsey Bill, wasn’t expected to be a full beat so they were not worried about being pushed inshore towards the lee shore of the Sussex coast.

The 1355 update, however, was more problematic, with a forecast of southerly winds Force 6 to Gale 8, locally Severe Gale 9, veering south-west. Periods of heavy rain. Moderate or poor.

“Although this sounded ominous there was little we could do about it,” wrote Blewett.

They later reduced sail to the same plan as the previous night, with the boat nicely balanced and making 4-5 knots.

Dover was the last viable port of refuge for Morning Cloud 3 in an onshore gale; skipper Don Blewett decided to continue. Credit: Getty

At around 2300, a few miles before reaching the Owers buoy, Morning Cloud 3 was struck by a big breaking wave that threw her down so violently that several laminated deck beams split and soon a foot of water was above the cabin sole.

Worse still, crew member Gardner Sorum was trailing astern, attached to the boat by his lifeline.

It was only after a head count five minutes later after Sorum had been hauled aboard, that it was realised Nigel Cumming was missing, his tether having broken.

They tacked back onto a reciprocal course in an attempt to find Cumming but failed to locate him in the dark and mountainous seas.

To compound matters, some crew had sustained injuries in the first knockdown , including Gerry Smith who had fractured one vertebrae and displaced three others.

After tacking back onto her original course, Morning Cloud 3 was struck by a second huge wave in a similar position to the first.

This one rolled her far enough to immerse the masthead in the sea.

Morning Cloud 3 was salvaged by a crew of a fishing vessel and bought into Shoreham. Credit: Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty

Christopher Chadd, Heath’s 22-year-old godson, had just emerged on deck but was not clipped on at that point and did not hear the warning shouted to him.

Every effort was made to throw him a line or a lifebuoy but all failed before contact with him was lost.

At the same time the injury list was growing, with Blewett having a broken shoulder blade and three ribs, one of which had perforated his lung, Sorum had also broken three ribs and his right arm was broken in three places.

By now the boat was badly disabled, with further structural damage to the deck beams; a section of coaming and toerail had been ripped away.

The forehatch – an oversized opening designed to facilitate rapid sail changes – was also missing, as was the port cockpit locker lid and the main liferaft stowed inside.

With water now waist deep in the saloon, there appeared every chance the yacht would founder if it encountered a third similar wave.

Blewett made the order to abandon ship, using the remaining four-person liferaft.

Despite the conditions and the injured crew, this was not as difficult as might be expected given the conditions, as the yacht was so low in the water the raft was at a deck level.

The five men then spent several hours in the raft, before being blown ashore on the beach at Brighton.

The raft proved stable until they reached the surf, where it was rolled and the occupants fell through the canopy.

Somehow they managed to put two of the most badly injured crew back in the raft, while the others guided it towards the shore, where onlookers waded in to assist.

The body of Christopher Chadd was found by helicopter shortly afterwards and a few days later local fishing boats snagged the severely damaged wreck of Morning Cloud 3 in 40ft of water, a couple of miles off Shoreham. She was towed to the harbour.

The subsequent inquest absolved everyone concerned from responsibility for the loss of Morning Cloud 3 and the sad deaths of Christopher Chadd and Nigel Cumming.

Heath’s boat was not the only one to encounter difficulties in the same storm: the RNLI’ s magazine The Lifeboat reported 66 launches, 57 lives rescued, and 21 vessels saved in the 48 hours from noon on 1 September, making it one of the busiest 48-hours in the RNLI’s history.

1. Navigation analysis

Of course, much has changed since 1974. Today we know our exact position at all times thanks to GPS and other GNSS systems such as Russia’s Glonass and the EU’s Galileo.

Nevertheless, at the time an error of navigation , putting the boat further inshore and closer to the lee shore than expected, was not thought likely to have been a contributory factor.

Today, few of us would think about setting sail in challenging conditions without a chart plotter to hand. Credit: Theo Stocker

A comment from RORC (that doesn’t identify the writer) at the end of the Seahorse article says: “It is impossible to be quite exact as to the position of a yacht in a Force 9 gale. But from John Irving’s account and from Don Blewett’s it is highly improbable that the yacht was inshore.”

Nevertheless, this was written looking through the lens of the mid-1970s – when only basic tools were available for navigation.

Today, being out in similar conditions without GPS and a chart plotter would be almost unconscionable, and for many of us properly scary.

The RORC commentator notes: “However, there is a bulge in the 10-fathom line, and there is always confusion in the seas further west, and these may have combined with the gale blowing straight onto the lee shore in creating unique conditions. The immediate lesson to learn… is respect for the power of the sea and the advisability of keeping – as far as possible – in deep water.”

Adlard Coles also picked up on this in his classic work Heavy Weather Sailing : “Granted that Casse Tete made the same passage without mishap, I think both boats would have been safer had they tacked to seaward immediately as the Owers light buoy opened on the port bow. The disaster underlines the RORC recommendation given after the Channel Storm of 1956, that ‘it is better to be out at sea in open water away from land influences where… she has the best chance of coming through without serious trouble.’”

2. Freak waves

Nevertheless, Coles added a final point, writing: “It has been argued that extra high waves from the synchronisation of wave trains should not be called freaks as they arise from natural causes, but as all seas come from natural causes this appears somewhat pedantic. It is the shape and steepness of occasional freak (abnormal) waves as well as their size which can do the damage. The addition of the Morning Cloud disaster to other mishaps described in this book may cause anxiety but I must emphasise that such occurrences are extremely rare and their number is infinitesimal compared with the countless safe passages made by yachts all over the world.”

For years, the scientific community looked in vain for proof of these rogue waves that have been reported by mariners since time immemorial.

Everything changed on 1 January 1995, when a laser measuring device on the Draupner oil platform in the North Sea recorded a wave height of 25.6m (84ft).

Although more rogue waves are being recorded, the chances of experiencing one while sailing are still slim. Credit: Image Professionals GmbH/Alamy

Minor damage inflicted on the platform well above normal sea levels confirmed the reading of the laser sensor.

Five years later, the RRS Discovery , a British research vessel, encountered a significant wave height (the mean height of the largest third of waves) of 18.5m (61ft), with individual waves up to 29.1m (95ft).

A 2004 study using three weeks of radar images taken by European Space Agency satellites found 10 rogue waves, each of which was at least 25m (82ft) high.

As the technology required to measure wave height has improved and become cheaper, more rogue waves have been measured, including one of more than 21m (69ft) at the southern end of the Chanel du Four off the cost of Finisterre in north-western France, during Storm Ciaran on 2 November, last year.

Rogue waves remain sufficiently rare; Coles is correct to note that the overwhelming majority of boat owners will never meet one.

Of the three enormous breaking waves I’ve encountered in 85,000 miles of sailing, the first was deep in the Southern Ocean, on passage from Auckland to Cape Horn, the second roughly 130 miles west-north-west of A Coruña in Galicia, well offshore in 4,000m of water while heading for the Canary Islands.

The third was closer to home, 10 miles south of the Lizard Point on the return leg of the 2019 Azores and Back Race.

This was in an easterly gale, created by high and low pressure systems squeezed together in close proximity, with mean true wind speeds of around 40 knots.

Had I not been racing on a very well-prepared boat for ocean sailing – and with a chance of a very good result – we would have diverted south to Brittany and enjoyed fine weather in Camaret-sur-Mer, where there was never more than 20 knots of breeze while waiting for conditions in the English Channel to moderate.

3. Better modelling

Weather forecasting has improved enormously over the past five decades.

It’s unlikely the crews of Morning Cloud 3 and Casse Tete would have continued past Dover, the last viable port of refuge in an onshore gale on that passage, and may well not have even left Burnham, had they had access to the data we now have available for medium-term forecasts.

Medium -term weather forecasting is improving in accuracy all of the time. Credit: Getty

The availability of ever more powerful supercomputers, along with step changes in science, means that medium-term weather forecasting has become progressively more accurate at the rate of approximately one day per year.

Today’s six-day forecasts are, on average, more accurate than the 48-hour forecast at the time of the 1979 Fastnet Race storm in which 24 yachts were abandoned out of an initial fleet of 303 entries, with the loss of 15 lives.

There are two aspects to a forecast: what is going to happen and when it’s going to happen.

In many cases, our forecasts today are good at the former, but predicting the exact timing of a weather front four or five days in advance remains a tall order.

We should, therefore, not be surprised if a feature that was initially forecast to come through overnight a week in advance actually takes place during daylight hours, or vice versa.

4. The importance of sea state

When passage planning it’s easy to be fixated on wind strength, but as the loss of Morning Cloud 3 shows, sea state is often a more important factor.

Today we are fortunate in having mostly reliable predictions of swell and significant wave height, though it must always be remembered that headlands, tidal races and relative shallows can create dangerous breaking waves that are out of proportion to those in adjacent areas.

It’s important not to underestimate the potential value of these wave forecasts.

Tidal data is just as important when passage planning as wind strength. Credit: PredictWind

It’s tempting to assume the IMOCA 60s used for the Vendée Glob e solo round-the-world race can cope with everything thrown at them.

However, before the finish of the last edition, several competitors slowed down on the approach to the Bay of Biscay, waiting for a potentially dangerous sea state to subside.

Wave forecasts were also used in the recent Arkea Ultime Challenge – a non-stop solo race around the globe in giant 100ft trimarans – where a couple of competitors deliberately slowed their boats ahead of the approach to Cape Horn, again to give time for dangerous seas to moderate.

There are important lessons in this for the rest of us.

5. Wind factor

Gusts of wind are invariably more difficult to handle than steady conditions and are often responsible for inflicting damage to yachts.

Gust predictions are therefore another useful aspect of today’s weather forecasting when passage planning in borderline conditions.

Again it’s important to remember that headlands , valleys and relatively narrow channels, such as the Needles Channel, can cause the breeze to funnel, creating stronger winds in these areas than the raw model output predicts.

Headlands, valleys and narrow channels cause winds to funnel, increasing the wind strength. Credit: Richard Langdon

It should be no surprise that the accuracy with which numeric weather forecasting can model the winds around geographical features is a function of the model’s resolution.

The UK MetOffice UKV (2km grid size) and French Arome (1.25km or 2.5km grid) are therefore better in this respect than the 9km ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) and 13km GFS (Global Forecast System) models.

However, even then the smallest geographic feature that can be modelled accurately is roughly five times the grid size.

That’s why forecasts with direct input from experienced meteorologists, such as the UK’s Inshore Waters and Shipping Forecasts, can still add significantly to our understanding of the conditions that can be expected.

6. Sail configuration

Questions were also raised at the time as to whether sailing with only a deep reefed mainsail, and no headsail, placed Morning Cloud 3 at greater risk of being overwhelmed by a big breaking wave.

There’s certainly a body of evidence for keeping a useful amount of speed on when sailing downwind in big seas, which makes the boat more responsive to the helm and therefore easier to keep stern-to the largest waves.

But Morning Cloud 3 was close reaching at the time and Blewett reported the boat was comfortable and well balanced under that sail plan.

So seems very unlikely that this was a contributory factor and I’ve not found mention of it in the contemporary literature.

There has been much debate as to whether the crew of Morning Cloud 3 would have been better using a headsail, rather than a deep reefed main. Credit: Richard Langdon

The 1979 Fastnet Race inquiry report canvassed all competitors involved to learn as much as possible from this disaster.

“No magic formula for guaranteeing survival emerges from the experiences of those who were caught in the storm,” the report states.

“There is, however, an inference that active rather than passive tactics were successful and those who were able to maintain some speed and directional control fared better.”

This report also revealed that several competitors experienced breaking waves coming from a very different angle to the rest, which chimes with my own experience in the North Atlantic.

These waves have the potential to cause a lot more damage than those more aligned with the main wave train.

Ensuring the crew can remain down below as much as possible in heavy weather is one way to mitigate risk. Credit: Group V team/PPL/GGR

Any time there’s potential for big breaking waves, anyone in the cockpit could be at risk.

Two of the competitors who died in the 1979 Fastnet were lost after being trapped in the cockpit of an inverted yacht.

In the mid-1980s the US Coast Guard commissioned a study using model and full-scale testing to investigate whether drogues could be used to prevent the capsize of yachts in breaking waves.

The report published in May 1987 concluded that ‘in many and possibly most cases’ a properly engineered drogue deployed from the stern of a fin keel sailing yacht can prevent capsize in breaking seas.

Don Jordan was one of the authors and the Jordan Series Drogue he subsequently developed has been successfully used by many ocean voyagers, including Jeanne Socrates.

In addition to reducing the risk of capsize, a yacht lying to a series drogue doesn’t need to be actively steered, so all the crew can be safely below decks.